Dyed-In-The-Wool History

Vietnam / Indochina

Jim Pederson December 10, 3034

Note: Two of the major sources for this essay are Greg Swanson’s Why The Vietnam War? Nuclear Bombs and Nation Building in Southeast Asia, 1945-1961 and Dr. Greg Poulgrain’s JFK vs. Allen Dulles Battleground Indonesia. In the bibliography and notes the original sources from these and other sources are preserved as they frequently go to original sources document and interviews conducted by these authors.[1]

Tonkin Gulf

On August 5, 1964, about nine months after the murder of President Kennedy, President Johnson presented to Congress the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution addressing two allegedly “unprovoked attacks” on two US destroyers from August 2 – 4. On August 7th the resolution was passed by the Senate 88-2 and by the House 414-0. Johnson signed the resolution on the 10th of August paving the way for direct US involvement in Vietnam (1) (2).

The actual chain of events that led to the resolution started on the night of July 30-31 when the South Vietnamese Navy attacked North Vietnamese radar installations on Hon Me and Hon Ngu islands in the Gulf of Tonkin. This was part of a larger operation conducted under oversight and direction of the US to attack military targets along Vietnam’s coast (3). The USS Maddox and the Turner Joy had been sent to the area to conduct reconnaissance operations in support of the South Vietnamese and the Maddox had been in the area and observed that North Vietnamese torpedo boats had been sent in pursuit of the South Vietnamese vessels and withdrew but returned the next day (3). On August 2nd the Maddox was approached by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats and fired warning shots which led to the torpedo boats returning fire at the Maddox that then called in air support from the nearby carrier Ticonderoga (3). In the resulting fight one of the torpedo boats was badly damaged and the Maddox escaped. Two days later communications were intercepted that were interpreted as a plan to attack the destroyer but were probably dealing with salvaging the stricken torpedo boat. The night was stormy and the Maddox and Turner Joy both reported that they were tracking multiple vessels approaching them from different directions and began firing and called in air support (3). Navy pilot Commander James Stockdale responded and reported seeing no torpedo boats. Captain John Herrick of the Maddox, after reviewing the available information sent a message stating, “Review of actions makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful. Freak weather event and overeager sonar men may have accounted for many reports…Suggest complete evaluation before any further action taken.” (3) (1) Johnson immediately authorized retaliatory attacks and a following intercepted communication that was a more detailed report of the events of August 2nd was misinterpreted as having confirmed an attack. (3)

While Americans at the time were generally well aware of the increasing US role in Southeast Asia going back into the Eisenhower administration this event would launch the country into another prolonged foreign war but this time without a clear objective leaving no path to victory and no definitive way out. In the years to follow this war would dominate the media, bring violent demonstrations to campuses, and generally tear the society apart starting a long continuing decline. The war would cause Americans to distrust the government and the related institutions as the result of having been lied to repeatedly by political and military leaders who continually assured us of progress and a “light at the end of the tunnel” only to be proven wrong over and over (4 p. 5). The only reasonable conclusion from this being that they were habitual liars or incompetent or some combination of the two.

The Tonkin Gulf incident was an exaggerated event that the US had a great deal to do with instigating that was then used to push a reluctant public to at least temporarily accept large scale military intervention. This same pattern occurred in the Mexican American War, the War Between the States, the Spanish American War, WWI, and WWII (19 pp. 60-1). This was a tipping point but the story started long before going back to WWII and even earlier and wasn’t limited to Vietnam but involved the entire region. It was rooted not just in political philosophy but economics and the strategic power struggle of the Cold War. The development of America’s role in Vietnam happened in the context of the dramatic shift in US foreign policy that occurred after the death of FDR and the Truman administration which was heavily influenced by the Rockefeller associated “Wise Men” within the Roosevelt administration (5) (6). It would also feature the conflict of two prominent American political families, the Kennedy’s and the Dulles’s, and two specific individuals Allen Dulles and John F Kennedy.

Above is a video of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara making the case for the Tonkin Gulf Resolution immediately after the August 4th incident. Much of what he said here was later established to be false.

The resolution itself is shown to the right

This is what brought US combat troops in Vietnam but the events that led up to this stretched across the prior twenty years.

FDR, Dulles, and Kennedy

FDR had consistently expressed views of a post war vision that was non-imperialistic and coupled with an economic structure that would not permanently impoverish developing currencies with weak currencies (7). It could be argued that this was really describing a US dominant economic structure as developed after the war couched in moral terms as has always been common for US politicians but his son Elliot Roosevelt documented his father’s views as conveyed to him prior to and during the war in his 1946 book “As He Saw It” which supports the idea that these were his genuine beliefs (7). This was done after FDR’s death and prior to development of the cold war so it’s difficult to find ulterior motives in his record. FDR was quoted as saying to Churchill regarding American’s attitude to imperialism, "understand how most of our people feel about Britain and her role in the life of other peoples... There are many kinds of Americans of course, but as a people, as a country, we're opposed to imperialism - we can't stomach it." (4 p. 25) (7) Roosevelt maintained good relations with Russia and was skeptical of the European allies but this was to change very rapidly after his death (6 p. intro) . The people who initiated this policy shift originated within his own administration and became deeply entrenched during the Truman administration forming the “Vital center” leading to the Korean War followed by regional conflicts around the world. This is viewed by many as a foreign policy disaster that shaped the world since then (6 p. 2).

Looking at the Kennedy’s, the family patriarch Joe Kennedy was a devoted anti-imperialist and isolationist. He was a key voice of the Old Right who JFK described as being “to the right of Herbert Hoover” (which was almost certainly true). JFK sounded very much like a committed cold warrior as he rose to national political prominence but it would be hard to imagine that his father’s views didn’t have some influence on his perception of the world. The Kennedy’s were also the first Catholic and Irish family to rise to the heights of US politics that was dominated by families of New England puritan background.

The Dulles brothers’ father was a Presbyterian minister from Waterford, New York. John Foster Dulles, who became Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, was five years older than Allen and their younger sister, Eleanor Lansing Dulles, was also a career diplomat. The Dulles family with their five children lived in a church parsonage, attended church nearly daily, and were homeschooled by multiple private tutors (8). John Dulles would remain generally true to the faith he was raised in while Allen would go on to have many extra-marital affairs and was not church affiliated as an adult. The two brothers remained competitive throughout their lives. Despite being the children of a minister, the family was prominent in American history with their maternal grandfather being Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison and their uncle Robert Lansing was Secretary of State under the Wilson administration. John Dulles married into the Rockefeller family (8). The family’s patriarch, Joseph, initially arrived in America during the 1770’s after having made a fortune in the Dutch East Indies most probably by trading in Opium and possibly slaves before the British East India Company came to control the trade (9 p. 9). This type of financial heritage was very common amongst prominent American families although the Dulles fortune was established before those of Perkins, Forbes, and Delano. The family’s original name was probably “Douglas” but was shortened to Dulles when Joseph was in the Dutch Indies. Both Allen and John Dulles were top lawyers for the Rockefeller oil empire during the 1920’s and 30’s as it was easy and accepted for prominent people to move easily between public and private enterprise. (9 pp. 8-10)

The chart to the left is intended to show how rapidly and dramatically US foreign policy shifted after the death of FDR. The seeds for the abrupt transition, however, were sown in the later days of his own administration by people who were part of the administration.

French Colonization and Indonesian Gold

The French took control of Vietnam in the 1850’s and then annexed neighboring Laos and Cambodia turning them into French colonies. They produced opium, salt, and alcohol and also mined zinc, copper, and coal along with creating rubber plantations (4 pp. 20-22). In addition to taking the resources they taxed the colony heavily (5). Although it is difficult to quantify living conditions it is generally believed that the people of Indochina lived in a state of pseudo slavery (10 pp. 91-95). There was periodic resistance against French rule but the colonizers maintained a network of informants to suppress any sort of organized opposition. (4 pp. 20-22) This situation remained fairly static until the run-up to WWII.

To the south of Vietnam in Indonesia, in the 1930’s Allen Dulles as part of his involvement with Standard Oil became aware of potential oil reserves and gold deposits. Indonesia is removed from Indochina but it is in the same region of the world and was also linked to European colonizing interests and to the developing conflict of WWII. The Japanese would come to occupy both places and were a threat to European and American interests. This would also become a major source of contention between Allen Dulles and JFK around the same time Vietnam policy was reaching a tipping point. In Indonesia in 1936, an expedition that was sponsored by the Dutch and two groups that were part of Standard Oil with whom the Dulles’s were closely tied, determined that at a high elevation there appeared to be a huge gold deposit (9 pp. 23-40). This was known but not advertised at the time and was later described as the world’s largest deposit of Gold but wasn’t mined until 1972. Greg Poulgrain describes the exploration in detail in the second chapter of JFK vs. Allen Dulles Battleground Indonesia. Poulgrain maintains that the secrecy was to prevent the gold deposit from falling under the control of a potential indigenous government and that this information was not disclosed to Kennedy.

The following paragraph from Poulgrain describes the level of secrecy and how long this was protected:

Post-war, Dozy (Jean Jacques Dozy, one of the three geologists who made the discovery) worked in South America. Only when two decades of political wrangling over New Guinea sovereignty seemed to be an issue well in the past did Dozy comment on his 1936 discovery that it “was just like a mountain of gold on the moon.” (11) It was not so much the remoteness that was in question but the fact that he acknowledged it was a “mountain of gold,” not a mountain of copper. Yet the policy of concealing the true concentration of gold in the Ertsberg did not stop. This policy, which had started at the time of the 1936 discovery and continued for decades, did not stop in 1972 when the American mining company Freeport Indonesia began production. Of course, this was no longer a matter of concern for the Dutch but for the Indonesian government, then and now. Ten years after mining began, Joseph Luns (former Dutch foreign minister from 1952 to 1971 and NATO secretary general from 1971 to 1984) informed me, in an interview in his headquarters in Brussels, that the Dutch government had unsuccessfully tried to gain American support to mine “the largest outcrop of base metal ever located.” (12) Luns declared: “The American companies had conversation with the Netherlands government but were prevented by the American government from pursuing it with the argument that the Dutch would be out of it.” (9 p. 81)

After the Fall of Western Europe to Germany in May of 1940 the Vichy government came to power in France. The Japanese occupied Indochina and turned it into their own colony but allowed the French to stay on to administer the region which allowed them not to commit resources to do this (4 pp. 22-24) (5). In 1944 after Eisenhower had landed in France, the Japanese felt that they could no longer trust the French and took over direct control of the area which was the event that first drew the Americans to Indochina. Some of the French were put in prison and others escaped to China (4 p. 25). The OSS sent Archimedes Patti (true name) to work against Japan and set up an intelligence unit in the area. Patti was aware of FDR’s anti-imperialist policies and complied with and even supported this direction. Foreshadowing what could follow, FDR had told the Russians that one reason he wanted to disband colonialism was to avoid future wars for national liberation (5). Under Japanese control the Vietnamese were forced to stop planting rice, and to start to grow peanuts and other oil seed crops instead, so that they could use them as byproducts for oil and lubricants in their machinery. This resulted in widespread famine (4 p. 24) (13 p. 160) FDR’s thoughts on the colonial occupation of Indochina were captured by his son Elliot Roosevelt in “As He Saw It” as follows:

"the Japanese control that colony now. Why was it a cinch for the Japanese to conquer the land? The native Indo-Chinese have been so flagrantly downtrodden that they thought to themselves: Anything must be better than to live under French colonial rule! Should a land belong to France? By what logic and by what custom and by what historical rule? I'm talking about another war, Elliot... I'm talking about what will happen to our world, if after this war we allow millions of people to slide back into the same semi-slavery!" FDR (4 p. 27; 7)

Operating under the non-imperialist vision, the OSS mission contacted rebel leader Ho Chi Minh to offer assistance and Ho met with Gen. Claire Chennault of Flying Tigers fame (4 pp. 31-3). For a time, Ho worked with the OSS which supplied him with small arms and even saved his life when he was sick with malaria (14 pp. 207-8). Patti was very impressed with Ho and wanted the USA to support him against Japan. Patti also met with Vo Nguyen Giap who would become the military commander of the Viet Minh (4 p. 41). The French had told the OSS that Ho was a "long-standing rebel, anti-French, of course, and strictly a Communist." OSS Agent Charles Fenn asked Ho about his allegiances, and Ho replied that the French said anyone who wants independence is a Communist. When Fenn asked Ho what he required in return for working with the OSS he said "Arms and medicine". Fenn created an OSS file for Ho, labeling him Agent 19 code name "Lucius" where he noted that he was "impressed by his clear-cut talk; and Buddha-like composure." (4 pp. 31-3) Patti approved OSS teams DEER and CAT to go into Vietnam to train Ho's Viet Minh forces to fight the Japanese but when they arrived they found Vo Nguyen Giap to be in charge in a rugged isolated area that the Americans had to parachute into. Gaip was 30 years old at the time, had a middle class background, had studied Vietnamese history and anti-colonial writings, and had been a school teacher. The teams brought American weapons and spent several weeks training the Vietnamese (4 p. 39). Giap had first met Ho in China and when he returned home, he discovered his sister and brother-in-law had been executed by the French for treason and his wife had been arrested by the French and she later died in prison. He told some French officials he was friends with that their government "destroyed my life." (4 p. 39)

Far left is a picture of Ho Chi Minh taken in 1957

Near Left is an image of

Vo Nguyen Giap taken in the late 1960's or early 1970's

The image to the far left is Archimedes Patti taken on station at the OSS field office in 1945

Near left is a picture of Allen Dulles from Jan 1965 taken at Harvard Business School

The French Return (Thanks to the British)

The Viet Minh never got a chance to fight the Japanese as Japan surrendered before this could take place. Once Japan was defeated the Nationalist Chinese were to occupy the north, while the British were to occupy the South. (Swanson, p. 48) This was to be a temporary arrangement until the Japanese were expelled prior to the unification of Vietnam. Ho and his followers had already designed a Vietnamese Flag and were working on a Declaration of Independence (5). The OSS had become the center of allied authority in the area and traveled to Hanoi to administer the transfer of prisoners and expected to preside over Japanese surrender and an orderly transfer of power with the French role limited to the transfer of people and prisoners but the situation quickly ran out of control (5). In Hanoi, Patti and Gap spoke for about an hour and Patti realized that the Soviet Union had not contacted any other Vietnamese. Patti wrote "Giap arose and with a warm smile which I found as I knew him better to be a rarity, and said, 'the people wish to welcome you and our American friends. Would you and your staff oblige us by coming to the front gate?'" General Giap told Patti, "this is the first time in the history of Vietnam that our flag has been displayed in an international ceremony and our national anthem played in honor of a foreign guest. I will long remember this occasion." (4 p. 50) (15 pp. 196-9) Patti then met with Ho who was still suffering from malaria and was posed with the question of how the United States would respond to a Vietnamese declaration of independence. Patti replied to Ho that he couldn't speak for the United States government and his role was to keep the people back home informed of events. Ho went on to explain that he was not a communist, or "an agent of the Comintern," acknowledged he was a socialist, and had worked with French, Chinese, and Vietnamese Communists. Ho said he had traveled to the Soviet Union but explained this saying "who else was there to work with?" He described himself a "progressive-socialist-nationalist." (15 pp. 199-203)From there the role of the OSS continued to weaken which Swanson described in detail in Why the Vietnam War?

In the North the Nationalist Chinese took control over what assets were left in the Bank of Indochina after having already been pillaged by the Japanese and went about buying the assets of the Vietnamese and French at drastically discounted prices (5). Under Japanese occupation the economy of Vietnam had collapsed resulting in mass starvation and those that survived were destitute. What happened in the South though was far worse. English Major General Douglas Gracey arrived in Saigon knowing virtually nothing of the history or current political situation and saw his role as transferring power back to the French (4 pp. 54-8) (15 p. 240). He came with a mixed battalion of Indian Gurkhas and English. His background briefing was actually provided to him by the French and upon arrival he completely ignored the Viet Minh (4 pp. 54-8). The OSS representative there was Lt. Colonel Peter Dewey (son of congressmen Charles Dewey) and when Gracey learned that Dewey was working with the Viet Minh he immediately berated Dewey and said that he was to be made aware of all his activities. A British historian wrote of this, “the activities of the OSS detachment were so blatantly subversive to the Allied command that within forty-eight hours of his arrival Gracey felt compelled to summon its chief, Lieutenant-Colonel Peter Dewey, to appear before him." (4 pp. 57-8)

Gracey’s first act was to arm the French POWs who took out their anger on the local population as opposed to following orders and reporting to rendezvous points. They looted homes and stores while drinking heavily and raised the French flag over public buildings (4 p. 58) (14 pp. 280-85) (15 pp. 315-17). Gracey shut down Vietnamese newspapers and radio stations and the French beat Vietnamese civilians and shot Viet Minh sentries. Dewey protested this to Gracey but got no response and was then told to leave Saigon while the chaos made news all over the world. The Viet Minh attacked the prisons, releasing all the prisoners. The British, realizing the situation they created, devised a plan that walked a line between a retreat and backing the French which would have been politically unacceptable. London determined that they would propose, "to get French troops into southern Indochina with upmost dispatch, and, after turning it over to them, to withdraw our forces as soon as possible." (13 p. 165) (4 p. 60) (15 pp. 309-320) Peter Dewey made arrangements to flee by plane. He sent a note to his superiors stating, "Cochinchina is burning, the French and British are finished here, and we ought to clear out of Southeast Asia." Dewey never made it out as he was accidently killed by the Viet Minh. As the situation continued to spiral out of control Gracey asked the Japanese Army to help fight the Viet Minh. Hundreds of Viet Minh were killed and Gracey left in late January of 1946 having altered the flow of history. The French returned and Ho tried to negotiate independence which failed as did a cease fire. (Swanson, p. 74) France began shelling Haiphong and occupied Hanoi. In December of 1946, Giap began an assault on Hanoi that was the beginning of the French Indochina War. Douglas MacArthur said about this turn of events:

“If there is anything that makes my blood boil, it is to see our allies in Indochina and Java deploying Japanese troops to reconquer these little people we promised to liberate. It is the most ignoble kind of betrayal. “(Swanson, p. 61)

The entire situation played out catastrophically for all involved, especially the United States. Archimedes Patti later wrote:

"Ho Chi Minh was on a silver platter in 1945…. we had him. He was willing to, to be a democratic republic, if nothing else. Socialist, yes, but a democratic republican. He was leaning not towards the Soviet Union, which at the time he told me that the USSR could not assist him, could not help him because they just — won a war only by dint of real heroism. And they were in no position to help anyone…So really, we had Ho Chi Minh, we had the Viet Minh, we had the Indochina question in our hand, but for reasons which defy good logic we find today that we supported the French for a war which they themselves dubbed 'la sale guerre,' the dirty war, and we paid to the tune of 80 percent of the cost of that French war and then we picked up 100 percent of the American-Vietnam War," (4 p. 62) (15)

Years later in 1973 Patti contacted the CIA to recover his old reports he had sent back to his superiors and from the responses he received it was clear that they had never been opened.

Upper left is a still shot of the Viet Minh shelling French positions (Britannica). Note the lack of uniforms or any sort of armor.

Above is a brief video of the fighting. The French had full air superiority but the Viet Minh had an extensive network of tunnels (Britannica)

To the left is a brief video of the Viet Minh entering Hanoi

Here is a link to a video on Reedit that can't be embedded of a Viet Minh frontal assault on a French position.

The Defeat of the French and the Domino Theory

The French established Bao-Dai, who they had a long standing association with, as governor (4 p. 74) (16 pp. 379-80). At this time Ho Chi Minh had about 60,000 active troops and a million local reserves. Giap was unsuccessful at taking Hanoi and fought a passive/aggressive war while increasing his forces. Stalin didn’t recognize Ho’s government until 1950 and China did likewise. Stalin told Ho “our surplus materials are plenty, and we will ship them to you through China. But because of limits of natural conditions, it will be mainly China that helps you." (4 p. 77) In 1950 France began to transfer administration to Bao Dai’s government. (17 pp. A-7)

By 1947 the rapid reversal of FDR’s anti-imperialist post war vision had been finalized with President Truman’s new Truman Doctrine, which was crafted by Dean Acheson and based around George Kennan’s Long Telegram, although the political debate would remain active for a few more years (5). Acheson’s public statement read:

“The recognition by the Kremlin of Ho Chi Minh’s communist government in Indochina comes as a surprise. The Soviet acknowledgement of this movement should remove any illusion as to the “nationalist” nature of Ho Chi Minh’s aims and reveal Ho in his true colors as the mortal enemy of native independence in Indochina.” Dean Acheson (Pentagon Papers) (17)

Following Acheson’s announcement, David Bruce, the U.S. Ambassador to France, cabled that it was time to deal with Vietnam "in a completely cold-blooded fashion." Acheson assembled a State Dept. working group that announced full support for the French stating that America must either support France "or face the extension of Communism over the remainder of the continental area of Southeast Asia and, possibly, further westward." (5) (4 p. 85)

By 1951 the French had suffered 90,000 casualties dead and wounded. In China Mao Zedong and his forces had defeated Chiang Kai-shek's Nationalist who evacuated to Taiwan. Laos and Cambodia were still firmly controlled by French backed governments. Even with the Truman administration giving tens of millions of dollars to support the French, Giap was in control of the countryside and was just 25 miles outside of Saigon (4 pp. 65-8). 1951 was also the year future president John F Kennedy visited Saigon with his brother Robert (Bobby). What they found was a war zone where virtually the entire population opposed the French. The next day Kennedy visited with Associated Press Bureau Chief Seymour Topping and then spoke with American diplomat Edmund Gullion and was told by both men that the French effort couldn’t succeed and that the war had turned the Vietnamese against the Americans. Kennedy’s concerns led the French to file a complaint with the American embassy. Kennedy made a speech upon his return warning of the folly of tying American interests to maintaining the French colonial empire (4 p. 68). The Cold Warrior counter argument to this was the “domino theory” holding that if one western supported government fell others would also follow in short order. In this case it referred specifically to Laos and Cambodia following Vietnam and separated the actions of the occupier from any sort of moral context. In 1957 JFK would give another speech dealing with French colonialism referred to as the “Algeria Speech” calling for Algerian independence which many see as completing his awakening on the subject. (5)

The opposition to the Truman and Eisenhower policies was the remnant of the anti-imperialist and isolationist Old Right that was largely defeated when Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower and the Rockefeller wing of the party. There were however still notable politicians like Berry Goldwater, who were apprehensive of the expanding Cold War. After Eisenhower took office the US support for the French war effort in Vietnam rose significantly. Senators Goldwater, Everett Dirksen, and Richard Russell objected to this and generally didn’t accept the whole domino theory argument. Goldwater stated of the Eisenhower funding request, “as surely as day follows night our boys will follow this $400 million” (4 p. 96). Senator Russell added: “You are pouring it down a rathole; the worst mess we ever got into, this Vietnam. The President has decided it. I’m not going to say a word of criticism. I’ll keep my mouth shut, but I’ll tell you right now we are in for something that is going to be one of the worst things this country ever got into.” (5) Senator John Kennedy proposed a substitute amendment that ordered that all money sent to Indochina "shall be administered in such a way as to encourage through all available means the freedom and independence desired by the people of the Associated States, including the intensification of the military training of the Vietnamese." It was defeated 17-64 after administration officials stated that they would work towards these goals. (4 p. 96)

Under Eisenhower the funding increased from tens of millions under Truman to hundreds of millions. The Domino Theory was a justification after the fact of a collection of policies and decisions that would not appear to make sense but there were also broader influences. The US was trying to make sure France stayed within the western NATO alliance (4 p. 96) and Vietnam was also part of the US vision for controlling the “third world” in a different sort of empire that is controlled financially and with the constant threat of military intervention and regime change. Around this same time the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) was starting to take shape led by Nassar in Egypt, Jawaharlal Nehru in India, and Sukarno in Indonesia which was of specific interests to the Dulles’s (9 p. 34). Under the Eisenhower administration Secretary of State John Dulles established a two-pronged strategy to deal with emerging nations and rising nationalism against European colonial powers that started slowly in the 1940’s but by the mid-50’s was spreading rapidly. The first step was to support the colonial power in retaining its control and then, if a independent nation did emerge, was to channel it into one of the anti-communist alliances America was creating around the world such as the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), the Baghdad Past, and the Rio Treaty (9 pp. 35-7). Any nation that failed to join one of these groups was against the United States and, therefore, communist and would be targeted by the CIA in a regime change operation. The initial meeting of NAM was held in Bandung, Indonesia in 1955. A year after the Bandung meeting Foster Dulles gave a speech titled “The Cost of Peace” where he condemned neutrality saying that the alliance system had made neutrality obsolete. (9 pp. 35-7)

The expanded funding the French received was of little value. Giap began the final phase of his war against the French by encircling the 16,000 French troops at Dien Bien Phu with 50,000 of his men. The area was a deep valley in a mountainous region near the Laotian border in northwestern Vietnam. The Chinese had provided Giap with 200 trucks, 10,000 barrels of oil, 100 artillery pieces, and advisors. Supporters traveled up and down the mountain path by foot and bicycle bringing supplies to Giap’s men (4 pp. 97-8). The Vietnamese dug a network of several hundred miles of tunnels and trenches surrounding the French and were able to move without exposure to French fire. The French pleaded for more assistance to avoid defeat and John Dulles, Vice President Richard Nixon and Admiral Arthur Radford were all supportive of this by either inserting American ground troops or the use of an air armada referred to as Operation Vulture that included atomic weapons (5). Eisenhower would only authorize Operation Vulture if the British would sign off on it but Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden wouldn’t go along. He didn’t see Vietnam as being worth the risk or effort nor did he agree with the domino theory. After being thwarted by Eden, Foster Dulles offered the atomic bombs directly to the French apparently without Eisenhower’s knowledge or approval but the French turned him down reasoning that the bombs would take at least as heavy a toll on their own troops. (David Talbot, The Devil’s Chessboard, p. 245) Dien Bien Phu fell in May of 1954.

This video shows the Viet Minh being welcomed as liberator when entering Hanoi in 1954

America creates South Vietnam

The United States now had to determine what their objectives really were and whether to accept defeat or devise an alternate strategy to regain control. Dulles, Radford, and other military officials met to assess the situation and the discussion focused on who would be the main power in Asia? In some ways America could now be seen as the heirs to Britain’s role in the “Great Game” for control of the region. Radford made clear that he saw America’s enemy in Asia as being China and that unless the US went after China, China and Chinese communism would control the continent (4 p. 109). At the meeting Dulles acknowledged that the Domino Theory wasn’t valid in Vietnam but saw a new mission in building an alliance against China. Nixon went along with this reasoning that a soft policy with China wouldn’t work. A plan was developed where the US at the upcoming peace conference would appear to go along with the settlement but would not allow for a vote unifying the country because they knew Ho Chi Minh would win the election (4 p. 114) (17 p. 106). This was intended to divide the country in two. The conclusions from the meeting were captured in a position paper that was taken to a full meeting of the National Security Council and approved as official policy on August 18, 1954.

Eisenhower, perhaps at this point was starting to push back against what he named the military industrial complex, had no interest in getting America involved in a war in Asia, and had said at a national security meeting a few days earlier that defense spending had already reached a maximum level (4 p. 122). Eisenhower stated that the nation had to be careful "to stick to a system of defense that could be sustained for 40 years if necessary, in order to avoid transforming the U.S. into an armed camp… If defense spending led to huge budget deficits, inflation could explode and the nation would be turned into a garrison state that demolished private enterprise as a result.” He then went on to say he was, “frankly puzzled by the problem of helping defeat local subversion without turning the U.S. into an armed camp.”

In spite of Eisenhower’s reservations, the plan stood. At Geneva the Chinese advised Ho to accept the partition plan to avoid fighting another Korean War against the US. From there the Dulles brothers took charge along with renowned black operator Colonel Ed Lansdale to create the new country of South Vietnam. CIA official Bob Amory picked Ngo Dinh Diem, who was strongly anti-French, as the new head of state which was approved by Frank Wisner and Allen Dulles. (4 pp. 128-9) Bao Dai, who the French had installed, agreed to appoint Diem and prime minister and Diem then denounced the Geneva Accords as non binding. Lansdale arranged an election were Diem got over 98% of the vote which included many districts where there were more Diem votes than registered voters (4 p. 128). The United States, and specifically the CIA, had created a new country and would own the problem they created until they were finally defeated and withdrew nearly 20 years later realizing Eisenhower’s worst fears.

Diem was managed by Lansdale (18 pp. 30-35) who devised a propaganda plan to transfer one million Catholics to the South to create supporters for Diem who was also Catholic (19 pp. 25-35) (19 p. 52) . Candidates for national assembly had to be approved by Diem (4 p. 159). The Can Lao party was headed by Diem’s brother Nhu and the two went about imprisoning tens of thousands they saw as posing a threat to their rule. This included a significant number of summary executions (19 p. 90). Diem’s presence in the US was increasing where he became at least somewhat popular but he was never popular in Vietnam in large part because he never did anything to improve the lives of the rural peasants. There was clearly a religious aspect to Diem achieving some degree of popularity in the US in much the same way that Chiang Kai-Shek and the Chinese Nationalists did in the years prior to WWII but Diem would have had broader denominational support (19 pp. 60-70) thanks to younger Catholics being attracted to cold war politics starting with McCarthy.[2] Diem also went to significant lengths to market himself to prominent people in the US (19 pp. 27-31) with the aid of American academic Wesley R. Fisher who acted as an advisor to Diem. Diem appointed province and district chiefs but did not redistribute land. Rather he moved peasants to unpopulated areas but did not give them title to the land while taxing them. From 1955 to 1961 the US gave the Diem government two billion dollars. There were alternatives to Diem but his public meeting law prevented them from garnering public recognition in Vietnam. Candidates that violated this law would face arrest on charges of conspiracy with the Viet Cong (Communist forces in South Vietnam). Dr. Phan Quang Dan was one of Diem’s most notable critics who was elected to the national assembly in 1959 by a margin of 6-1 despite Diem sending 8,000 soldiers to vote against him. When he went to take his elected seat he was arrested on fraud charges (20 pp. 114-6). This was so egregious that a group of opposition Vietnamese leaders and politicians met at the Caravelle to draft and sign a letter of protest. One of the signers was Phan Huy Quat who had been recommended to Eisenhower as a better alternative to Diem. This generated some press coverage in the US but thanks to Diem’s restrictions on the press, it was ignored in Vietnam. (20 pp. 114-6)

Above left we see Ngo Dinh Diem taking office and declaring South Vietnam to be an independent country.

To the left Dinh meets with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal_Nehru in 1957.

Above is a map showing Vietnam in relation to Laos, Thailand and Cambodia

Indonesian Outer Island Rebellion

In 1958 the Outer Island Rebellion took place in Indonesia where two Indonesian Army commands in Sumatra and Sulawesi attempted to break away from the central government in Java. This was supported by the CIA but there may have been more to this than would initially meet the eye. The plan was hatched after President Sukarno visited both the United States and Russia in 1956 and wound up taking foreign aid from the Soviets. To the Dulles’s this confirmed that he was a communist. On September 25th of 1957 President Eisenhower issued a directive to plan a coup against Sukarno.

70% of Indonesia’s export revenue came from the outer islands and this was growing (9 p. 176). US Ambassador Allison observed “the dissatisfaction of the regional leaders over the domination of the Central Government by the Javanese and the fact that while the regions, particularly Sumatra and Sulawesi, produced the vast majority of the foreign exchange the nation received, only slightly more than ten percent of it was spent in the regions.” (9 p. 176) (21 p. 301) Indonesian President Sukarno had sought to keep the vast archipelago together but had been unsuccessful at resolving Indonesia’s territorial dispute with Dutch New Guinea. The Communist Party in Indonesia (PKI) got most of its electoral support in Java from landless peasants who were typically rice farmers who were hoping for land reform. PKI got 16% in the 1955 election and was expected to increase their support in the coming election in 1959 that was postponed due to the uprising (9 p. 178). The world and most significantly Moscow saw the rebellion as a CIA sponsored plan to split Sumatra and Sulawesi off from Java with the perception being that the US saw Java going communist. An alternate view, however, is that this was really intended to create a centralized command in Jakarta as opposed to regional and fairly autonomous commands that could then be used to oust the Dutch and take control of the government (9 p. 178). The CIA commander in charge of the operation was Frank Wisner had a reputation of failure including the attempted Hungarian revolt two years earlier. The analyst credited with coming up with this plan was Guy Pauker who was with the Rand Corporation and then started his own consulting firm (9 pp. 181-4).

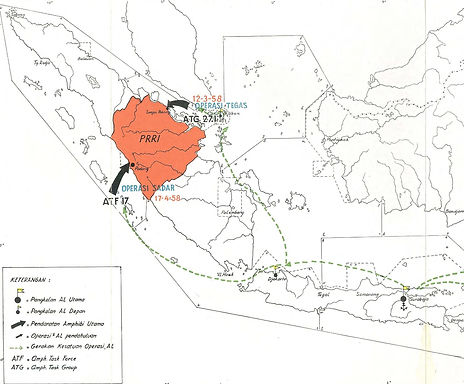

The rebellion started in February and seemed to have strong US support including naval presence from a task force from the 7th Fleet referred to as Task Force 75. Task Force 75 included an aircraft carrier but when the rebels requested air support all they got were two aging B-26’s flown by retired RAF pilots that exploded in mid-flight(it could never be confirmed if they were shot down or not) and never reached their targets (9 pp. 238-42). Support trickled in and one large weapons drop was intercepted. The conflict went on for three years with the defeat of the PRRI occurring in September of 1961. Throughout most of the conflict there was limited US support but never nearly enough to alter the outcome. The Indonesian government had initially approached the US for arms to fight the rebels but were denied. They then turned to the Soviet Union which became their major arms supplier allowing Indonesia to rapidly modernize and expand their military capabilities and strengthen the Indonesian position with respect to the Dutch (9 p. 190).

It is a fact that the US intervened to encourage the Outer Island Rebellion. It is known and openly acknowledged today and it was known at the time. The historical question is whether the CIA’s failure was due to incompetence and bad decision making or if the failure was intentional in pursuit of a bigger objective that couldn’t be reached without this intermediary step. Many who have studied the events and others who participated in them have reached the later conclusion. Dr. Greg Poulgrain presents this case in detail in his book JFK and Allen Dulles: Battleground Indonesia.

%2C_Jalesveva_Jayamahe%2C_p241.jpg)

This map is a little difficult to without color but it the area of conflict in the Outer Island Rebellion and also gives a view of the vastness of the archipelago and some of the inherent difficulties in controlling this area.

Laos

Only a few weeks after taking office JFK set up a task force on Laos that included academic and anti-communist, Walt Rostow, Assistant Secretary of State for the Far East J. Graham Parsons, Dean Rusk, and newly appointed Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, Paul Nitz. At that time Laos didn’t have a strong central government, hosted several armed factions, and was home to the Pathet Lao who were aligned with the North Vietnamese and Chinese. In Why the Vietnam War, Swanson devotes a good amount of coverage to Rostow because of his influence. Rostow was a staunch advocate of direct US involvement in Vietnam and was broadly influential. At Harvard and MIT he was from his earliest days an avid critic of Marxism and communist doctrine. While at Harvard he was part of the Center for International Studies (CENIS) that was a think tank promoting US global dominance (4 p. 194). While being a Democrat he was discouraged by Eisenhower’s refusal to commit ground troops to save the French at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. He wrote a number of books, the most well known of which was Stages of Economic Growth which was intended to show that economic progress in the Third World would not lead “to a communist end game utopia, but to a corporate capitalist end point” (4 p. 196)

In a meeting on March 20, 1961 Rostow argued that the US should send troops into neighboring Thailand that could be readily deployed to Laos. This was as much a diplomatic bargaining chip as a military strategy. The Joint Chiefs opposed this reasoning on the grounds that the North Vietnamese and Chinese could simply poor troops into Laos which could lead to a massive land war in Asia. Kennedy decided against this plan but decided rather to put a task force on Okinawa. He then went on TV and “declared to the American people, and the world, that a superpower confrontation in Laos was now at hand” (4 p. 236). Sitting in front of a map of Laos he concluded by saying, "The security of all of Southeast Asia will be endangered if Laos loses its neutral independence. Its own safety runs with the safety of us all - in real neutrality observed by all…..I know that every American will want his country to honor its obligations to the point that freedom and security of the free world and ourselves may be achieved." (4 p. 237) (22 pp. 310-11) (18 pp. 20-24)

Laos was a tiny landlocked nation established by the Geneva Convention of 1954 that didn’t have so much as a single railroad. The ambassador to Laos in 1954, Charles Yost, who only lasted 18 months there having lost 20 pounds due to severe dysentery, noted that 98% of the population lived self-sufficiently in remote areas with little contact with the government (4 p. 240). Laos actually had a history of neutrality and had no natural tendency to align with either faction in the Cold War. The main political entities in Laos were the Royal Laotian government, the Pathet Lao, and the remnants of the French regime there. Prince Souvana Phouma wanted to avoid involvement in the Cold War. Prince Souphanouvong, his half brother, was the leader of the Pathet Lao concentrated in the northern part of the country. Because of this relationship, the prince thought he could form a relationship with the Pathet Lao, but Washington had no use for this following the doctrine advocated by Allen Dulles that those who weren’t on the American side were communists. This was all somewhat puzzling as there was so little to fight for in Laos.

US foreign aid had gradually become a primary policy tool which was a prelude to nation building. The US started sending $40 Million a year to Laos in military aid and $10 million in developmental aid. Much of this was consumed by corruption and was hoarded by a local ruling class which has remained a consistent issue ever since in other areas. Part of this involved an artificial exchange rate where government officials that controlled imports and exports imposed an exchange rate of 35 kip (Laotian currency) to one US dollar when the real market rate was much less than that. This allowed importers to buy goods using currency purchased from the Laotian government at a third of if real value and sell the goods locally at a fantastic margin (4 p. 242). The corruption got a good deal of press coverage in the US including in Reader’s Digest which had very wide circulation at the time and the Americans administering the program were entirely isolated from the Laotian people.

Souvana Phouma travelled to the US in January 1958 after Ambassador Parsons visited Laos. He said that the Pathet Lao, despite receiving support from the Chinese and North Vietnamese, were not communists and went on to say "neither by temperament, civilization, nor social traditions predisposed to communism." They were simple farmers and without a "dissatisfied peasantry or urban proletariat" (4 p. 240) In spite of this Allen Dulles set up a CIA output there with a 22 person staff with Henry Hecksher as head of station. They invented the Committee for the Defense of National Interests (CDNI) which ultimately forced the prince to resign as Prime Minister and he was replaced by the CDNI backed Colonel Phoumi Nozovan in December of 1959. The military mission there then expanded to 515 men (5).

When Kennedy came to office he asked ambassador Winthrop Brown (current ambassador to Laos) for his opinion on US policy in Laos. After Brown started to recite official positions Kennedy stopped him and said that he wanted to hear his opinion. Brown told him he favored a neutral position with Souvana Phouma and Kong Le. On April 15, 1961 Phoumi launched an assault against Kong Le and the Pathet Lao across the Plain of Jars that failed. Kennedy was under heavy pressure for direct intervention in Laos at that point but chose to ignore the Joint Chiefs of Staff appeal, that was presented by Arleigh Burke and supported by Vice President Lyndon Johnson and included the use of atomic weapons against China if they intervened (18 pp. 24-27) (5). He did move a naval armada into the area and the Pathet Loa then called for a cease-fire. Kennedy said of this later, “It it weren’t for Cuba, I might have taken this advice seriously.” After that a showdown with China was still very possible but it would have to be in Thailand or Vietnam but not in Laos.

This news clip shows the US naval deployment to the area in 1963 and features Kennedy making remarks on Laotian sovereignty. It in he tries to answer the question for Americans as to why such a dispute half a world away that most had now knowledge of should be of concern.

Indonesia 61-63

When Kennedy came into office as opposed to going down the path of regime change in Indonesia, he sought to draw President Sukarno back into the US orbit through targeted foreign aid. In reviewing the case file of Allen Pope, who was a CIA pilot shot down during the rebellion in 1958 and held captive since, JFK seemed to gain a deeper understanding of what had gone on there saying, “No wonder Sukarno doesn’t like us very much, he has to sit down with people who tried to overthrow him (9 p. 38).” (the file he was given was redacted) Sukarno visited Washington in May of 1961 but the discussions with JFK would first have to address a territorial dispute with the Dutch regarding Dutch held West New Guinea which was also referred to as West Irian. When Sukarno arrived Kennedy asked him, “Why do you want West Irian?” noting that Melanesians were a different race (9 p. 295; 23). Sukarno responded, “it is part of our country; it should be free.” President Kennedy, being familiar with the area from his experiences in WWII, countered that the Solomon Islands and New Guinea seemed to be the same race and shared a common culture and history. Sukarno’s deputy First Minister Leimena then responded that they were the same culture and went on to explain why although his explanation was nuanced and only partial true. Kennedy then went on to inquire about conducting a popular vote but Kennedy’s influence in the matter at that time was at best indirect as the issue had been handed over to the Dutch and the UN which for Kennedy transferred a serious Cold War problem away from the US.

JFK had met with the Dutch Foreign Minister Joseph Luns two weeks prior to meeting with Sukarno (9 p. 292). Kennedy had questioned, “why the Dutch were so concerned about this faraway island which was really a great burden for them” (9 p. 294) (24) not knowing of the mineral rights associated with this land. Luns pointed out to Kennedy that the Dutch were disappointed and shocked that the United States withdrew from their previously accepted invitation to participate in the inauguration of local self-government councils in New Guinea. There were other political considerations that played into this but the five to ten year plan the Dutch had proposed for self-governance was also a major factor in the decision.

Over the next several months JFK attempted to keep the Indonesians from taking direct military action against the Dutch including sending a personal letter to Sukarno but by December the Indonesians decided to act. This is influenced by the US vote on two recent UN resolutions that left the Indonesians in doubt as to US support. The campaign was known as “Mandala” and was led by Shuarto who would replace Sukarno a few years later. This mobilization did lead to the two countries starting bilateral talks. The US sought to resolve the matter quickly while allowing the Dutch to save face (9 p. 308).

On January 15th of 1962 there was word of a military confrontation between three Indonesian motor patrol boats (MTB’s) and two Dutch destroyers that occurred at 10:30 at night 12 miles of the southern coastline. The Dutch intercepted the three MTB’s killing 57 on board including the mission commander Yos Sudarso. The Dutch captain was a former classmate of Sudarso’s. Why he was on the boat was something of a mystery with one report being that he disagreed with the mission and wanted to accompany his men. In that the Dutch only had three destroyers to begin with to patrol a fairly vast area it is unlikely that they would have been able to precisely locate the MTB’s . A more probable explanation is that the commander of the Mandala operation, Suharto, contacted Clark Air Base in the Philippines and the Americans then notified their NATO ally the Dutch (9 p. 309). Although this may have initially been seen as siding with the Dutch that was not intent. JFK had no plan of becoming involved in this dispute on the Dutch side stating, “We have all the potential wars we need at the moment, and we do not consider it useful to become involved in this dispute. From the strategic point of view, we believe that West New Guinea as such is of little consequence, since if the Communists have Indonesia the additional territory does not alter the strategic position.” (23). In the ensuing peace talks Ellsworth Bunker, as past-head of the International Red Cross, became the mediator. Bunker, who was previously associated with Allen Dulles, not only failed to allow for Papuan self-determination but moved up the handover to full Indonesian control to May 1, 1963. By moving the date forward the expiration date for the lease on the Ertsberg gold deposit fell outside of Dutch control. It is not known if Bunker was in contact with Dulles during the negotiations. (9 p. 313) It should be pointed out here that the Indonesians would still have a great deal of economic entanglement and dependency on Dutch business and the degree to which the natural resources of the area would benefit the native population remained somewhat uncertain.

With the Sovereignty dispute resolved Kennedy intended to close on cementing the relationship with Indonesia. When he first took office in 1961 a CIA briefing paper advised, “we should not now entertain any major increases in the scale of economic or military aid to Indonesia.” (9 p. 330) but that was exactly what he was doing. Events at this point started to overlap the Cuban Missile Crisis which was a more urgent and dangerous matter and there was still nothing to indicate that either Kennedy or Sukarno had become aware of the immense quantities of gold, copper, and oil in the interior of New Guinea. From the perspective of Allen Dulles the struggle for control of the resources entered another phase, one that he had foreseen and prepared for. There was a three year low level conflict between Indonesian forces and the British in Malaysia along the border of Sarawak referred to as Konfrontasi that was about to get dialed up. (9 p. 315)

Konfrontasi started or dramatically expanded in December of 1962 as the result of the Brunei revolt and it was portrayed at the time that Indonesia had a role in initiating this but Dr. Greg Poulgrain extensively investigated this incident many years later and established that this was definitively untrue. In 1991 Poulgrain interviewed Brunei’s friend Azahari who has typically been identified as the specific individual who started the revolt. Azahari denied doing this and Poulgrain was able to validate his account in the British archives which, in turn, enabled him to identify the person who really did start the revolt which was Roy Henry of Special Branch, British Intelligence. Poulgrain interviewed Henry later that year in London where, faced with the evidence, he confirmed that he had started the uprising and arranged for Azahari to be blamed for it (9 p. 317) [3]. The plan worked as Sarawak aligned with Malaysia. This also related to control of the Brunei oil fields and political control of Singapore under Lee Kuan Yew who was closely aligned with the British. The rebellion was further aided by CIA agent William Andres Brown (who later became ambassador to Israel) who provided arms to a Sarawak communist group known as the Clandestine Communist Organization (COO). Dulles had not informed Kennedy of any of this.

The problems created by the Malaysian situation brought Kennedy’s aid plan to a halt and Dulles’ removal from his position hadn’t weakened his power due to an extensive network of supporters in the CIA and other government agencies (9 pp. 330-1). JFK’s vision for Indonesia ran contrary to the Dulles’ strategy in two key respects that were irreconcilable. JFK intended to use the army as “servants of the state” not as a center of political power. Secondly he intended to leave Sukarno in power. Dulles had planned to use the Army in a coup to remove Sukarno. Kennedy’s plan to resolve the funding problem along with the Malaysian situation and other issues was an official visit to Jakarta early in 1964. The visit, of course, would never happen. Sukarno was removed in a coup not long after Kennedy’s death.

This is a brief video on Konfrontasi that gives an overview of the conflict and the area involved but doesn't address the specific events that started or expanded it.

Conclusions

Kennedy didn’t want to arrive at a final position on Vietnam and the possibility of sending US combat troops there until the Indonesian problem was resolved but it appears that he had long since departed from the policies originally laid out for him by the Intelligence and military communities and most other advisors in his administration. In Vietnam his path was different from that of the Dulles’ as he sought local civilian control of the government and the economy. After the Bay of Pigs he turned away from the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other entrenched government figures and sought input from speech writer Ted Sorenson, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and military aide General Maxwell Taylor (5). When Lyndon Johnson visited Vietnam in May of 1961, Diem declined American combat troops but asked for more funding. In July of 1961, Diem changed his mind and said he would accept American troops (4 p. 326) in what would become the Strategic Hamlet program. In late 1961Kennedy sent Walt Rostow and General Max Taylor to Vietnam and they predictably came back with a recommendation to insert US ground troops. Kennedy struck this from their report and told the press that no such recommendation was made. While Rostow and Taylor were out of the country, JFK met with his father’s friend journalist Arthur Krock. He told him “that he had serious doubts about the Domino Theory and did not think the USA should get into a land war in Asia” (5) (4 p. 335). In two meetings in November Kennedy determined that there would be no combat troops deployed to Vietnam but he did agree to more advisors and equipment. Virtually everyone around JFK other than the people previously mentioned wanted to go to war and the Joint Chiefs sent Kennedy a memo saying that his decision would lead to the collapse of Southeast Asia.

Less than two months before Kennedy’s assassination, Arthur Krock wrote:

The CIA's growth was 'likened to a malignancy' which the 'very high official was not even sure the White House could control ... any longer.' 'If the United States ever experiences [an attempted coup to overthrow the Government] it will come from the CIA and not the Pentagon. The agency 'represents a tremendous power and total unaccountability to anyone.' (25)

In contrasting Eisenhower and Kennedy a critical difference between the two was the degree to which the two elected chief executives were effectively captured by the Joint Chiefs, their cabinets and staff, and their broader stakeholders and influences. Both Kennedy and Eisenhower started off with what would appear to be solid “cold warrior” credentials while both also had non-interventionist influences. In the case of Eisenhower this would be from people associated with Senator Taft and the Old Right that became part of his administration like George Humphrey (26 pp. 125-6). Eisenhower was also fairly measured during his military career in terms of the use of force and the initiation of conflict. For Kennedy his own father was a staunch isolationist and key spokesman for the Old Right and from his father, JFK also had associations with people such as Arthur Krock. During their respective administrations, both were under fairly intense pressure to conform to the prevailing will of those they were surrounded by yet JFK was able to separate from them based on his experiences and observations to a greater extent than Eisenhower ever did.

President Eisenhower had a history throughout his administration of appearing hawkish on foreign policy matters but towards the end of his presidency he appeared back away from policies of confrontation. He had organized a summit meeting with the Soviet Union in 1960 that was ruined when an American U-2 was shot down during the meeting and the pilot captured [4]. During the 1960 campaign Nixon distanced himself from Eisenhower while Kennedy continued to attack Ike for the supposed “missile gap” that was later determined to not have been real. He had tried to control defense spending and the arms race but failed as he summarized to his son the day after the 1960 election saying, “all I've been trying to do for eight years has gone down the drain.” In his last National Security Council meeting, he wondered, “Can free government overcome the many demands made by special interests and the indulgence of selfish motives?" In his last act during his farewell address he made the famous reference to the “military industrial complex”. He expressed private concerns over “heavy spending leading in the direction of authoritarian government” yet he never forcefully challenged the unelected powers that surrounded him. (4 p. 261) (27 pp. 217-29) (28 pp. 192-5)

As Eisenhower looked upon Kennedy taking office he feared the possibility of an exploding arms race and those fears didn’t necessarily seem unwarranted but events took JFK down a different path that he had to take almost alone at many points as he struggled against what we now commonly refer to today as the “Deep State”. Was this the result of fundamental strength of character or simple pattern recognition from having been lied to repeatedly or was it as author James Douglas suggest in his book, “JFK and the Unspeakable” the result of some form of spiritual awakening. (29) Regardless of how he rose above the “Deep State” it wasn’t to become a pattern as one chief executive after the next would wind up virtually trapped by those around them.

This is the full farewell speech from Dwight Eisenhower which warns of the "Military Industrial Complex". He sees a potential future where the government could become central to all forms of endeavor and also addresses the permeant mobilization status of American society. Eisenhower points out that this could last for an extended period of time and also sees it as a threat to the fiscal health of the country. He does identify Communism as an existential threat but also expresses hope for a peaceful future.

The role of religion is also potentially significant but difficult to quantifiably assess. In his book, American Miracle Man in Vietnam, author Seth Jacobs presents a strong case that religious and cultural changes in America coming out of WWII enabled the cold war and its related policies to find broad support in the US electorate. He starts off the second chapter of his book by saying:

Less than a year after the United States inaugurated the atomic age by obliterating Hiroshima, and before the term cold war entered the world’s political lexicon, General Douglas MacArthur likened America’s growing competition with the Soviet Union to the ordeal of Jesus at Gethsemane. MacArthur, head of the U.S. occupation government in Japan, forecast an American victory over the communists because, as he put it, “Christ, even though crucified, nevertheless prevailed.” (30 p. 66) When the USSR exploded an atomic bomb in 1949, the evangelist Billy Graham warned his fellow Americans that communism was “against God, against Christ, against the Bible. . . . [It] is inspired, directed, and motivated by the Devil himself, who has declared war against Almighty God.” (31) In the spring of 1954, after the Eighty-third Congress voted to add the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance, Representative Louis Rabaut justified the amendment by declaring, “You may argue from dawn to dusk about differing political, social, and economic systems, but the fundamental issue which is the unbridgeable gap between America and communist Russia is a belief in Almighty God.” (32 p. 50) For the soldier, the preacher, and the politician—as well as for millions of other Americans at midcentury—the conflict with international communism was in essence a holy war. (19 p. 60)

He then went on to provide historical context stating:

Such convictions were not unique to the period. Americans have traditionally conceived of their national mission in religious terms. John Winthrop told the band of Puritans he led to New England in 1630 that “the God of Israel is among us. . . . The Lord will make our name a praise and glory.” (33 pp. 65-66) Abraham Lincoln claimed to “recognize the hand of God” in the Civil War. (34 p. 218) Both Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt asked for God’s help in their war messages to Congress. (35) Rarely, however, has the identification of America’s cause with God’s been made more explicit than during the Eisenhower years. America in the 1950s was, in one historian’s phrase, “God’s Country,” an avowedly Christian superpower engaged in a global contest with an adversary whose chief distinguishing feature was its atheism. (36) (19 pp. 60-1)

American, and specifically Yankee, culture has without a doubt always tended to present economic and political goals in moral and spiritual garb creating the impression of a noble national enterprise that provided initial justification for one aggressive war after another. It’s also inarguably true that many political and religious figures coming out of WWII presented the developing Cold War and the conflicts that went along with it as a sort of 20th century crusade where Christianity and Western Liberalism became merged. Looking at this from a later point of reference that saw liberalism evolve into neo-liberalism this alignment would seem inconceivable but at the time to many, perhaps most, it seemed reasonable and this sort of thinking remains a cornerstone of “American Exceptionalism” today. Jacobs contends that America’s religiousness hit a low point between the wars which enabled acceptance of progressive and even Marxists philosophies and then starting around 1950 a new awakening occurred that moved the window of allowable opinion dramatically to the right. Based on the political narrative reflected in American media and institutions this case can be strongly supported but when the question is applied to the overall population it becomes more nuanced.

American religious participation flattened slightly between the wars at around 52% but didn’t move backwards as it did following the War Between the States (37 p. 23). After the war it started to expand again but this was more gradual than abrupt and some of it was dependent on mass media which tended to create believers that were more shallow or transient than in previous eras. The nature of the church affiliated populations did however shift fairly substantially. Progressive Protestant congregations started to lose followers not just in percentages but in absolute numbers. Those who left frequently wound up in Evangelical churches that were drifting increasingly towards fundamentalism that held to a dispensational eschatology that adapted itself readily to the Cold War narrative seeing Russia as Gog and Magog and was also strongly pro-Zionist. Not all groups adopted this, such as Lutherans and Church of Christ, but most did and this sort of thinking extended beyond churches into popular media. Most significantly though, American Catholics grew in numbers and significance and were becoming supporters of the Cold War seeing Russia as an existential threat to the faith. Senator Joseph McCarthy certainly played a role in this but the Catholic presence in conservative media like National Review was at least as important.

Prior to the US actually entering the Vietnam War in 1964 the national polling services didn’t capture support for US involvement in Indochina but when this was polled, support was initially very high with a Gallup poll in 1965 showing 60% of the population approved and this number rose sharply to 72% in 1966 before then falling off rapidly and consistently after that. From this it is safe to assume that the electorate throughout the 1950’s and early 1960’s was strongly in favor of the course the US government was taking at the time and probably would have favored US troops in theatre well before this actually came to pass. Some demographic data on support for the war was taken but unfortunately it didn’t include religious affiliation. Christians and especially conservative or Evangelical Christians weren’t seen as a voting block at the time but the available evidence would seem to suggest that prior to 1968 the Cold War and the Vietnam War specifically was to a certain degree a national religious endeavor which would impact culture, religion, and politics for decades to come.

This picture from 1956 is of John Foster Dulles and his son Avery Dulles who would become a Cardinal in the Catholic Church. Note the the Dulles family (Allen and john and the the three other siblings) were the children of a Presbyterian minister.

Catholics following WWII grew in number (percentage) and significance in society. They also became more religious and more conservative politically. They largely saw communism as an existential threat to the faith and supported the Cold War.

Protestants were leaving the more liberal denominations and moving towards Evangelicalism which also tended to favor Cold War policies and place them in a religious context.

Bettmann/CORBIS 1 June, 1956

Footnotes

[1] There are a relatively small group of authors who have specialized in the history of the Cold War, Vietnam, and the four assassinations. Their work is unusually thorough generally having to work around institutional barriers relying on original sources and interviews with principals. Some were involved in the events of which they write. They were generally part of the old left of the time (which is quite different from today’s new left) and hold a high view of FDR, his policies while president, and his post war vision.

[2] US public support for the war after the US became fully involved varied heavily by the year of the survey reaching a peak of 70% in 1967 according to Gallup and plummeting after that Invalid source specified.

[3] US public support for the war after the US became fully involved varied heavily by the year of the survey reaching a peak of 70% in 1967 according to Gallup and plummeting after that Invalid source specified.

[1] The pilot was Gary Powers who was later released

Bibliography

1. Tonkin Gulf Resolution 1964. National Archives. [Online] August 7, 1964. https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/tonkin-gulf-resolution.

2. Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Britannica. [Online] February 13, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Gulf-of-Tonkin-Resolution/additional-info#history.

3. Bauer, Pat. Gulf of Tonkin Incident. Britannica. [Online] February 13, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/event/Gulf-of-Tonkin-incident.

4. Swanson, Michael. Why The Vietnam War? Nuclear Bombs and Nation Building in Southeast Asia, 1945-1961. New York : Campania Partners LLC, 2021.

5. DiEugenio, James. Kennedy's and King. [Online] May 1, 2021. https://www.kennedysandking.com/reviews/why-the-vietnam-war-by-michael-swanson?utm_source=FFF+Daily&utm_campaign=8a8e0fa741-FFF+Daily+05-24-2021&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_1139d80dff-8a8e0fa741-317316945.

6. Costigilola, Frank. Roosevelt's Lost Alliances. 2012.

7. Roosevelt, Elliott. As He Saw It. New York : Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1946.

8. Blake, Henry. Meet the Kleptocrats: How Two Brothers Undermined Democracy in America and the World. Medium. [Online] March 11, 2024. https://medium.com/@henryblake_48596/meet-the-kleptocrats-how-two-brothers-undermined-democracy-in-america-and-the-world-b1e31c22e198.

9. Poulgrain, Greg. JFK vs. Allen Dulles; Battleground Indonesia. New York : Skyhorse Publishing, 2020.

10. Scott, James C. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Substance in Southeast Asia. New Haven : Yale university Press, 1976.

11. Mining the Richest and Most Remote Deposit of Copper and Gold in the World: In the Mountains of Irian Jaya, Indonesia. Mealey, George. 1996, Freeport - McMoran Copper and Gold, p. 71.

12. Dr. J. A. M. H Lus, Sec General of NATO. [interv.] Greg Poulgrain. July 17, 1982.

13. Karnow, Stanley. Vietnam: A History. New York : Penguin Books, 1991.

14. Bartholomew-Fies, Dixee. The OSS and Mo Chi Minh: Unexpected Allies in the War against Japan. Lawrence Kansas : University of Kansas Press, 2006.

15. Patti, Archimedes. Why Vietnam: Prelude to Americas Albatross. s.l. : California University Press, 1980.

16. Gibbons, William. The US Government and the Vietnam War: Executive and Legislative ROles and RElationships Vol. 1. Camden New Jersey : Princeton University Press, 1986.

17. Papers, Pentagon. The Pentagon Papers Vol.1. Washington DC : National Archives, 1971.

18. Newman, John M. JFK and Vietnam; Deception, Intrigue, and Struggle for Power. Charleston : Creaet Space Independent Publishing Platform, 2016.

19. Jacobs, Seth. America's Miracle Man in Vietnam. Durman : Duke University Press, 2004.

20. —. America's Miracle Man in Vietnam. Durham : Duke university Press, 2004.

21. Allison, John M. Ambassador from the Prairie: Or Alice in Wonderland. New York : Houghton - Mufflin, 1973.

22. Schlesinger, Arthur M Jr. A Thousand Days. Boston, Mass : Houghton Mifflin, 1965.

23. Keefer, Edward C. Foreign Relations of the United States 1961-63. [Online] April 24, 1961. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v23/d172..

24. —. Foreign Relations of the United States 1961-1963. [Online] April 10, 1961. https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1961-63v23/d162..

25. Krock, Arthur. The Intra-Administration War in Vietnam with High-frequency Disorderly Government. New York Times. October 3, 1963.

26. Rothbard, Murray N. The Betrayal of the American Right. Auburn, Alabama : Ludwig Von Misses Institute, 2007.

27. Rust, William. Before the Quagmire: American Intervention in Laos 1954-61. Lexington Kentucky : University Press of Kentucky, 2012.

28. Swanson, Michael. The War State: The Cold War Origins of the Military Industrial Complex and the Power Elite. South Carolina : Create Space, 2011.

29. Douglas, James W. JFK and the Unspeakable. New York, New York : Simon & Schuster, 2008.

30. Lafeber, Walter. America, Russia, and the Cold War 1945-2006. s.l. : McGraw-Hill, 2006.

31. Christians, Muslims, and Hindua: Religion and USA South Asian RElationships 1947-54. Rotter, Andrew. 2006, Diplomatic History, p. 396.

32. Hudnut-Beimler, James. Looking for God in the Suburbs. New Jersey : Rutgers University Press, 1994.

33. Winthrop, John. A Model for Christian Charity. New York : s.n., 1998.

34. Wills, Gary. Under God. s.l. : Simon & Schuster, 1991.

35. Merrill, Dennis and Patterson, Thomas. Major Problems in American Foreign Relations. Boston : s.n., 2000.

36. Oakley, Ronald J. God's Country: America in the Fifties. s.l. : Barricade Books, 1986.

37. Stark, Rodney and Fink, Roger. The Churching of America 1776-2005 - Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy. Piscataway, New Jersey : Rutgers University Press, 2005.