Dyed-In-The-Wool History

The Cold War in China and Korea 1940 – 1954

Jim Pederson January 20, 2025

The events in the Cold War in Europe in 1949 and 1950 went favorably for the west with the success of the Marshall Plan rebuilding Western Europe and the Berlin Airlift that was a major defeat for Stalin. Events in Asia, however, were not at all favorable for the West. This in turn led to prolonged conflicts with no real end game or way out. Decision making on the part of US leadership was heavily influenced by the “China Mirage” of a westernized and Christianized nation that was sold not just to the American public but its leaders.

As the Cold War picked up steam during the McCarthy era, “communist” was used as a general label for anybody or anything that fell outside of the bounds of US corporate liberalism. The sort of “communist” in China and the rest of Asia that were prevalent were leaders of masses of peasant farmers who sought land reform and redistribution from what was very similar to a feudal system.

This poster is from the 1930's in Eastern Europe but it depicts one of the underlying identity issues with Marxism. It shows an urban factory worker with an agricultural peasant. The economic theory of Marxism was built around an industrial society while the peasant was representative of a condition that was constant across human history. The peasant sought land reform and this was far more characteristic of the Cold War conflicts in Asia. On one hand this could be and was cast as a communist / capitalist conflict but it could just as easily be seen in a creditor / debtor, of land owner / renter context. The US cast its lot with a small land owner class that had frequently been aligned with foreign colonial interests.

The Vision of a Westernized and Christianized China

Before, during, and after WWII the American public held a vision of a Christianized and westernized free China that was being led by a Christian convert, a sort of modern Asian Constantine, Chiang Kai-Shek. This image was created by the “China Lobby” that consisted of influential people tied to Chinese missions and Chinese trade that in turn had deep ties to the US media and the government and had been heavily supported by Protestant congregations across the country. The key family in creating this image was the Soong family that sprang from a Chinese immigrant laborer who became associated with and was mentored by American Businessman Julian Carr and the two jointly went about “winning China for Christ”. As unlikely as all this sounds, one of Soong’s daughters Ailing, would become the face for the China Lobby and would be a regular guest at the White house. Charlie Soong’s son T.V. Song would become friends with FDR and key people in his administration.

Chiang’s nationalist were defeated in a civil war at the end of WWII and wound up fleeing off shore to Formosa or Taiwan despite massive public and private support from the US and Mao’s China wound up aligned with the Soviets but the sequence of events that led to this were by no means unavoidable or unforeseeable. They are in many ways remarkably unusual and difficult to explain, much less defend. Ultimately the Nationalist were defeated because they lost the support of the people of China by their own actions and no external intervention could have changed that. Instead of building a nation they created “a military masquerading as a nation” with military spending accounting for 70% of total expenditures that was directed at internal as opposed to external enemies. (1 p. 139)

To understand what happened at the end of WWII and the beginning of the Cold War we must first look back at the history of the region. From the 1700’s western, primarily British and American, commercial interests dominated China. Because there was a much higher demand for Chinese goods in the west than western good in the east this created a crippling balance of payments problem that was resolved by the illegal importation of Opium into China using criminal gangs. From this prominent families in America became extremely wealthy and this strongly contributed to the industrialization of America. One of those families was the Delano’s who were FDR’s maternal grandparents. Over time the increased Opium flow into China destroyed China morally, culturally, and economically. When the Chinese government tried to stop this it was put down with force first in the Opium Wars and then in the Boxer Rebellion after which time China was effectively a failed state run by warlords. The western merchants and missionaries were concentrated principally around Canton and along the Yangtze River while Chinese peasants lived in abject poverty in the interior regions. By the early 1900’s this created a nationalist movement led by Dr. Sun Tse and that movement came to be controlled by sisters Ailing and Mailing Soong after their father died who then formed an alliance with Chaing Kai-Shek who drew his support from merchant families and warlords.

The missionary presence in China was not particularly effective at generating converts especially in the interior but did produce several generations of people who lived between the two cultures and some became politically and economically prominent in the US including Henry Luce who was the editor of Time and Life magazines and author Pearl Buck. Along with Luce and others in the media, Ailing who married Chiang Kai-Shek in a political union that required him to leave his first wife and to profess to convert to the Methodist denomination, and her brother T.V Soong created a westernized image of China and were very effective at fund raising for the Nationalists. While originally aligned with Mao, Mailing devised a plan to turn on him and wipe Mao and his supporters out but Chiang could never control the interior where Mao drew his support. The funds from the US were not used to convert the masses or to fight the Japanese but were mainly used to try to eliminate Mao.

To the Left is a very well known wedding picture of Chiang Kai-shek and Mayling Soong (Madame Chiang Kai-shek). This was a political union, designed by Ailing Soong that required Chiang Kai-shek leave his wife. They would become perhaps the most well known and influential political couple in the world during this time period.

The image to the left is of young Chinese immigrant laborer Charlie Soong who would become one of the wealthiest and most powerful people in the world. His story was almost too implausible to believe yet it happened

The image below is of the Soong sisters, Charlie Soong's daughters, who were the core of the Chinese Nationalist movement. Mayling Soong, who would marry Chiang Kai-shek and be a regular guest at the White House was the public face while Ailing Soong was the strategist and organizer. Chingling Soong would eventually align with Mao against Chiang.

The China Lobby, Chinese Civil War, and War against Japan

T.V Soong first gained access to the White House through Roosevelt advisor Felix Frankfurter, who would later become a Supreme Court justice and founded the ACLU. Soong and FDR had much in common with both having been born in to very wealthy upper-class families, both attending Harvard, and both being quick-witted communicators with similar styles. Soong however, had lived in both countries and knew how different China was from what FDR and other Americans perceived it to be (1 p. 152). Morgenthau had no knowledge of China or the Far East and generally accepted his friend’s presentation of it as fact. FDR also projected himself to be knowledgeable based on his grandfathers’ merchant history there (which was based around the Opium trade) but lacked any real knowledge either. Not knowing something and being aware of it can always be corrected but not knowing something and being certain you do can’t. Mayling Soong reformed Chinese virtues and history into an American context that missionaries and preachers could communicate to their target audiences in America. This included campaigns specifically focusing on changing or reaching specific elements of Chinese society so the appeal was tangible and specific (1 p. 170)

In July of 1937 the Japanese expanded from Manchuria into central China taking Beijing which was the ancient center of China and the home of the “Son of Heaven”. Mao wanted Chiang’s forces to fight the Japanese in northern and central China. In a disastrous decision, however, Chiang decided to take on the Japanese in the south of China in Shanghai. This is thought to have been primarily for public relations purposes as there were more Americans there with the goal being not so much to defeat the Japanese but to draw the Americans into the war (1 pp. 175-6). The Asian war became the first media war to be fought to control US public opinion even if it meant going against sound military decisions but it would by no means be the last. It should be clearly noted here that what was going on in China at this time was a civil war and a war against an external invader where the two parties in the civil war would to some extent cooperate against Japan although Mao’s forces did the bulk of the fighting. The fighting was a rout but was heavily covered in the press and had the intended effect. Steven Mosher summarized this in “China Misperceived” saying, “The new images of the Chinese provided by Pearl Buck and others could not have come at a better time. When a few years later the Japanese escalated their piecemeal attacks to all-out war, it was not the nameless, faceless masses of China who took up arms against the invaders, but Buck’s Noble Chinese Peasants.” (2 p. 146) In a speech a few weeks later known as the quarantine speech FDR raised Chiang’s hopes and encouraged more suicide stands but these led to nothing. While the American public favored the Chinese Nationalist there was no interest in entering the conflict. (1 pp. 178-9)

In late 1938, Harry Price, who was the founder of a China Lobby committee with a collection of high profile people, asked the original wise man, Henry Stimson to join his committee and he accepted (1 p. 188). The committee, known as the American Committee for American nonparticipation in Japanese Aggression, over the next two years would convince the American public that oil exports to Japan could be embargoed with no reprisals. Harry Price gave the group an American missionary face and Stimson was made honorary chairman which was a huge coup for the Soong’s and Chiang (1 p. 188). They were not only embedded in the Roosevelt administration but had as a figurehead leader one of the most influential people in the country. The committee cranked out a continual stream of press releases that weren’t only spread in the media but by churches and church affiliated organizations across the country. Morgenthau fully bought into the idea of embargoing oil and other materials to the Japanese but FDR rightfully feared that doing so would force the conflict south into Indonesia.

Above: This is an image of TV Soong with FDR in the White House during WWII (Roosevelt Archive)

This is a video from Smithsonian of the invasion of Shanghai. It points out that Shanghai was an international city with a large British and American presence. Chiang's forces were decisively and quickly defeated but it did receive extensive American press coverage. This was a battle fought for western media consumption.

This image of TV Soong is from 1945. Soong, like FDR was a Harvard graduate, and both came from family money. T.V Soong first gained access to the White House through Roosevelt advisor Felix Frankfurter and also became closely associated with Secretary Morgenthau and many others in the Roosevelt administration. (Roosevelt Archive)

The image to the left is of Japanese Special Naval Forces in the battle of Shanghai in 1937. Mao wanted Chiang’s forces to fight the Japanese in northern and central China. In a disastrous decision, however, Chiang decided to take on the Japanese in the south of China in Shanghai. This was done principally for media purposes. (Britanica)

Chiang wanted money to fight Mao while FDR believed Chiang needed money to fight the Japanese. American funding was especially important in that Stalin’s Russia had been providing support for Chiang in the form of low interest loans, all forms of military equipment, and advisors in order to protect Russia’s eastern flank from Japan but with a German conflict in the west becoming more likely, they could no longer afford this. The Treasury Dept proposed a loan of $35 million dollars that Hull solidly opposed having determined that Chiang was incompetent and corrupt (1 pp. 191-2). Morgenthau contested Hull’s position saying, “I am taking the liberty of pleading China’s cause so earnestly because you have three times told me to proceed with the proposals for assistance to China. All my efforts have proved of no avail against Secretary Hull’s adamant policy of doing nothing which could possibly be objected to by an aggressor nation.” (3) Morgenthau arranged a meeting with Roosevelt that Hull could not attend because he was at sea and got the loan proposal approved. Hull learned of this four days later. (1 pp. 193-4) Roosevelt’s new direction in China policy would now guide events and it wasn’t just not debated; it was also unannounced. The China lobby saw the loan as only the beginning in an anticipated chain of cash infusions. The China Lobby had taken over FDR’s own household with Sara Delano Roosevelt being chairwoman of both the China Aid Council and American Committee for Chinese War Orphans and Eleanor Roosevelt being honorary chairwoman of Pearl Buck’s China Emergency Relief Committee.

Roosevelt came to believe there was a real chance of Japan controlling China and that the loss of China would free Japanese troop strength to go after Indonesia and Southeast Asia so the Chinese conflict came to take on strategic as well as political implications. The US transferred its Pacific fleet from California to Hawaii to convey a message of deterrence to Japan. Admiral James Richardson argued against this saying that this would only provoke the Japanese. Roosevelt’s response was. “Despite what you believe, I know that the presence of the fleet in the Hawaiian area has had, and is now having, a restraining influence on the actions of Japan.” (1 p. 201) (4 pp. 38-9) Japanese admiral Isoroku Yamamoto interpreted this a bit differently. He told a colleague, “The fact that the United States has brought a great fleet to Hawaii to show us that it’s within striking distance of Japan means, conversely, that we’re within striking distance too.” (1 p. 201) (5)

Roosevelt increasingly became caught in a political trap largely of his own doing. The Republican candidate running against him in 1940 was Wendell Willkie who took an isolationist position portraying FDR as a warmonger and making claims like “You may expect war by April of 1941 if [Roosevelt] is elected” (6 p. 254) and Willkie was gaining in the polls. Democratic leadership was concerned enough about this that they urged Roosevelt to take a strong and definitive non-intervention stance. Contouring this Roosevelt appointed two interventionalist Republicans more in the mold of the eastern establishment or Rockefeller wing of the party, Henry Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretary of War and Secretary of the Navy. These nominations were made on the eve of the Republican convention and were politically expedient but in doing this he created a cabinet where both the right wing and the left wing, led by Morgenthau, were aligned against him specifically on the issue of China. (1 p. 202) The Soong’s and Chiang were completely aware at this point that FDR and Secretary of State Hull had no intention of supporting them either directly or indirectly but they were now in a position to work around that by effectively controlling FDR’s cabinet which was increasingly anti-Japan. The China Lobby and the Stimson committee led the passage of the National Defense Act signed on July 2nd, 1940 which gave the administration control of valuable natural resources. Stimson saw this as a potential measure to be used against Japan while FDR still had no intention of cutting Japan’s oil. (1 pp. 201-2) Meanwhile the American public was strongly in support of the Chinese, which they equated with Chiang, and still opposed intervention believing that they could have one without the other.

Through this entire time period there were no negotiations with the Japanese and they had no real access to US officials. A major reason for this was that the US support for the Chinese resistance, as they had been led to perceive it, was so strong that it was politically risky for Roosevelt. Ambassador Currie had established to Chiang, representing FDR, that in order for him to obtain Lend-Lease funding he would have to commit to fighting Japan, unite with Mao, cut military expenditures, and remove feudal elements from his government. He was unwilling to do these things (1 p. 241). Mao, on the other hand, was fighting the Japanese with a good deal of success, most notably the hundred regiment offensive in August of 1940 when he sent 430,000 of his troops against 830,000 Japanese troops in Northern China defeating them in a battle larger than the US had ever participated in. Mao continued to attract recruits as opposed to conscripts (1 p. 218).[1] The idea that China and the Nationalist leadership in particular were longing to become New Deal liberals was unique to the US. Foreign diplomats less inclined to cast reality in philosophical terms were all aware of this.

In Spring of 1941 Roosevelt agreed to negotiations with the Japanese but Secretary Hull would have to conduct them in secret. Hull’s negotiating counterpart would be Admiral Nomura who was the Japanese ambassador. Hull made clear initially that this was a discussion and not a formal negotiation and his goal was to get the Japanese to agree to agree to withdrawal from China reversing what had been the US position for the previous 30 years. It was further hoped that this would bring about regime change in Japan. The two men had a good deal of difficulty communicating with each other and often guessed at what the other was saying. Nomura had a proposed agreement that would retain Japan access to China that he thought Hull agreed to but he didn’t and this was later taken as a change of position (1 pp. 257-9). Ultimately the negotiation didn’t get anywhere and may have worsened or further confused the situation.

In May of 1941 Roosevelt established the Office of Petroleum Coordination headed by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes who was aligned with Morgenthau on Japan. He sought a way to go around Hull and was vocal in his criticism of the Secretary of State. In June of 1941 FDR had a personal loss that was largely hidden from view but was none-the-less very relevant. Missy LeHand, who was FDR’s longtime secretary, companion, and mistress (in effect she was his “other wife” and biggest fan) suffered a severe stroke. He not only lost emotional support but lost the person who managed his schedule and affairs (1 p. 261). Hours later Germany invaded Russia and Roosevelt had little knowledge of what was really happening there for an extended period of time. Deputy Secretary of State Sumner Wells was the subject of homosexual ethics allegations but Roosevelt had stood by him expending “political capital”. Finally Secretary of State Hull had just left on a six week vacation to White Spring Virginia and left embattled Deputy Secretary Wells in charge. Hull had become increasingly frustrated with Roosevelt who was relying more on Harry Hopkins (1 pp. 261-2). It was a perfect storm.

On July 8th the second contingent of American mercenary aviators left for China and the Japanese were well aware of where they were and what they were doing (7 p. 104). US code breakers decrypted a Japanese diplomatic communiqué on July 2 where the Japanese leadership had determined to occupy the southern half of Indonesia. Roosevelt told Welles to draft a resolution to freeze Japanese assets but stopped short of implementing it. FDR then explained to the public for the first time in a speech why he wasn’t suspending oil deliveries to Japan. His message was an acknowledgement that he was effectively appeasing Japan to avoid a war in the Pacific but the public had already been sold on the notion that oil could be cut off without causing a war. (1 pp. 265-6) The Executive Order freezing Japanese asset was issued on July 26th.

Roosevelt was fully engaged with what was going on in Europe and Russia and thought he had walked a fine line between cutting off oil and starting a US war in Asia and appeasing the public and members of his own administration having out maneuvered Stimson, Morgenthau, and Knox. At an August 5th meeting, with Hull and FDR still unavailable and Hopkins in Moscow, Acheson, Morgenthau, and others under them devised and implemented a plan to go against FDR’s oil policy. They would not process the requests without specifically disapproving them but the mechanism they set up to do this was complicated enough the it took Hull some time to figure it out even after he returned on August 11th. Quoting James Bradley, “History well notes the insanity of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor but little notes the insanity of the so-called Wise Men—focused on the China Lobby mirage—who provoked it.” (1 p. 271)

On December 7th 1941 Pearl Harbor was attacked. Just a few hours before that the Japanese under General Hirofumi Yamashita landed 20,000 troops on the east coast of Malaysia and moved south (1 pp. 285-6). Many thought at the time and continued to believe that there was some risk of Japan invading the west coast of the US which was lightly populated at the time but there was never any intent or capability to do this [2]. It is also commonly believed that FDR knew in advance of the Pearl Harbor attack but chose to let it occur in order to create an event to bring the US into the war. This goes against a good deal of evidence but the US may well have tried to create an incident off the Philippines (8) in relation to the Japanese move towards Southeast Asia.

[1] Both Mao and Chiang had torture centers and were guilty of human rights abuses – this was China.

[2] There were gun placements installed at west coast locations especially around Southern California, mandatory blackouts imposed, and camaflogue spread over industrial facilities.

This video link from the Roosevelt Archive is one of a number of home movies shot by Missy LeHand. LeHand was FDR's long time secretary and companion. The video shows some scenes from the White house but other are simply of family gatherings.

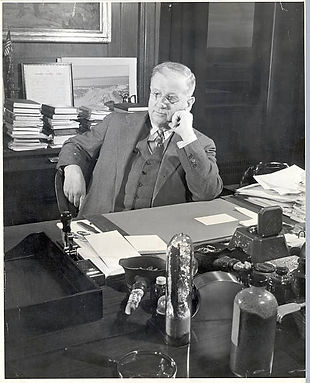

In May of 1941 Roosevelt established the Office of Petroleum Coordination headed by Interior Secretary Harold Ickes (shown tot he left) who was aligned with Morgenthau on Japan. He sought a way to go around Roosevelt and Secretary of State Hull and was vocal in his criticism of the Secretary of State.

All three of these pictures are from Getty Images.

Below is an image for FDR with Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau. Morgenthau was a long standing key advisor to the president but was also a strong supporter of the China Lobby and also sought to implement his own policies with regard to China.

The image above is of Secretary of State Cordell Hull from Tennessee who was the longest serving Secretary of State from 1933-44. Hull, along with FDR, was against cutting off oil supplies to Japan for fear they would then seek to obtain oil and other raw materials from Indonesia and Southeast Asia which proved to be correct but he was increasingly isolated within the administration. He was eventually "out smarted" by Morgenthau, Acheson, Ickes, and others who effectively did cut off oil to Japan through a permitting process.

Chiang, FDR, and Mao during WWII

General Charles Stillwell was appointed the commander of the Asian Theatre for the US. After initially meeting Chiang he told a reporter, “The trouble in China is simple: We are allied to an ignorant, illiterate, superstitious, peasant son of a bitch” (9 p. 134) In his diary he referred to Chiang as “Peanut” and said, “Chiang Kai-shek has been boss so long and has so many yes-men around him that he has the idea he is infallible on any subject.… He is not mentally stable, and he will say many things to your face that he doesn’t mean fully or exactly.” (10 p. 80) In February of 1942 a Gallup poll showed that 62 percent of Americans favored focusing the major military effort against Japan supporting the vision of a new China while only 25 percent saw Europe as the priority (11 p. 331). The China Lobby propaganda campaign didn’t slow down after the war started but continued unabated. (1 p. 299)

By 1943 there were some American journalists that were questioning the American vision of China. Reader’s Digest and the New York Times ran articles entitled, respectively, “Too Much Wishful Thinking About China” and “Our Distorted View of China.” (1 p. 308) The Chinese Army was described as “a comic opera chorus” and Chiang’s government described by saying “China was ruled by “old war lords, in new clothing, for whom war is a means for personal aggrandizement and enrichment,” and that the American public had been fed a mirage by “missionaries, war relief drives, able ambassadors and the movies.” (12) (13) This, however, would have little impact on Public opinion as beliefs that are arrived at casually with little investigation also tend to be held deeply especially when they can be leveraged for political and economic gain. The China fantasy would remain firmly in place all the way through the early 1960’s and is still defended by some writers and commentators today.

In July of 1944 following D-Day in Europe FDR forced Chiang to allow US officials to contact Mao. A US contingent including the OSS, US military personnel, and “China Hands” (longer term China diplomats), like John Service, traveled to Yan’an. Each sought an ally and both wanted China to unify. (1 p. 309) By summer of 1944 it was clear Mao’s followers were growing and Chiang’s were leaving him (deserting in many cases). Mao told Service, “The fact is clear… that China’s political tendency is towards us.… Chiang holds the bayonets and the secret police” over the people and was “determined on Communist elimination… Chiang Kai-Shek was elected President by only ninety members of a single party… even Hitler has a better claim to democratic power.” (1 p. 310) Mao didn’t see support coming from the Soviet Union due to the enormous losses they had suffered and was reaching out to Roosevelt. Mayling Soong also appeared to be separated from Chiang by this time due to numerous affairs and she and Ailing were living in a seventeen room River Oaks mansion in the Riverdale section of New York City. Ailing maintained the committee’s finances and fundraising while Mayling focused on the media. (1 pp. 312-13)

In the late summer of 1944 FDR dispatched Ambassador Hurley to Chungking to mediate between Chiang and Stillwell. At the same time he was using a private citizen, Oklahoma oil lawyer Patrick Hurley to circumvent the State Department. It is not clear what Roosevelt’s direction to Hurley was but the ambassador wrote later that the policy he was following was “is to prevent the collapse of the National Government” and “to sustain Chiang Kai-Shek as President of the Republic and Generalissimo of the armies.” (1 p. 313) (14 p. 94) Stilwell and the “China Hands” made clear that they disagreed and intended to work with Mao. James Bradley notes, “In retrospect, Stilwell’s advice could well have resulted in a lasting friendship between China and the United States, saved millions of lives, and averted the Chinese civil war, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War.” (1 p. 314) Hurley, who was not knowledgeable on China and in line with the China Lobby, cabled Washington that he was encountering opposition from “un-American” elements. (15 p. 95)

While Roosevelt’s directions to Hurley are not certain apart from Hurley’s account, FDR was clearly annoyed with Stilwell saying the general’s approach in dealing with Chiang was “entirely wrong” (1 p. 314). This left Marshall standing between his subordinates, who were entirely fed up with Chiang, and his boss the president who still saw Chiang as the sole leader of “one of the greatest democracies in the world” (said in a press conference with Madame Chiang) (1 pp. 314-5) Marshall generally had a very difficult time trying to explain FDR’s position on China without sounding ignorant on one hand or insubordinate on the other. Roosevelt’s cumulative beliefs and experiences were never displaced with objective facts. John Service, who was born in China and spent most of his life there, was less politically constrained than most, perhaps not grasping the hold the “China mirage” had on the people and the political process. A US official warned him against speaking openly about what he knew saying, “Jesus, Service! I read that thing of yours, and I certainly agree with you but it is going to get you in a lot of trouble.” (1 p. 316) (16 p. 150)

Concerned that the truth was not getting to the President, Mao attempted to reach out directly to Roosevelt. Major Ray Cromley, who was chief of the US mission in Yan’an forwarded a message to US Army headquarter in Chunking saying “Mao and Zhou will be immediately available either singly or together for exploratory conference at Washington should President Roosevelt express desire to receive them at White House as leaders of a primary Chinese party.” Zhou Enlai observed, “Hurley must not get this information, as I don’t trust his discretion.” The message, however, was intercepted, rewritten, then embedded in a 13 page cable described by Bradley as follows:

“Unknown for decades was that U.S. Navy technicians led by Captain Michael Miles intercepted and decoded the message sent to Chungking and shared it with Dai Li, the head of Chiang’s gestapo. Miles and Li rewrote the memo to make it appear that Mao was attempting to discredit Hurley in FDR’s eyes. On January 14, Hurley buried Mao’s invitation deep in a turgid thirteen-page cable to the White House, saying that he had been delayed by a plot hatched “within our own ranks” to undermine his efforts at a Chiang-Mao reconciliation. If Hurley had not heroically discovered this plot, “it would be futile for us to try to save the National Government of China.” All would soon be well in China, Hurley assured FDR; he was fully in charge, and Chiang and T. V. Soong were “now favorable to unification… and agreement with the Communists,” and after Hurley’s negotiations succeeded, Roosevelt could meet with both Chiang and Mao. In the meantime Hurley urged FDR to get Churchill’s and Stalin’s approval for “your plan for… a post-war free, unified democratic China.” (17) Dai Li also gave Ambassador Hurley fabricated accounts of John Service’s efforts to undermine him. When Service returned to Chungking from the U.S., Hurley warned him, as Service later remembered, “If I interfered with him he would break me.” (17) (1 pp. 318-9)

To summarize; the original communication was altered then buried in a longer document, falsehoods were conveyed as fact, actions were recommended that the originators knew would fail, an innocent man was threatened to keep him from speaking, and the crime then covered up. Mao oversaw an empire of one hundred million people yet FDR was sticking by Chiang as the post war leader and got Stalin and Churchill to go along and Mao would have to be forced to accept Chiang. This would ensure a civil war and other secondary effects that would have been hard to foresee. There were plenty of senior American officials that shared the fantasy like General Wedemeyer who wrote to the Joint Chiefs that Mao could be put down with small assistance given to Chiang’s government. Joe Alsop who was a distant relative of FDR and tied to the China Lobby wrote of Service and John Davies saying they were “childish to assume that the Chinese Communists are anything but an appendage of the Soviet Union” (while Stalin was supporting Chiang). (1 pp. 320-1)

The image tot he left is of General Charles Stillwell apparently enjoying a moment of levity with Chiang Kai-shek and Mayling Soong (Madame Chiang Kai-shek). Stillwell made no secret of his thoughts on Chiang, who he referred to as "Peanut". In his diary he said of Chiang, Chiang Kai-shek has been boss so long and has so many yes-men around him that he has the idea he is infallible on any subject.… He is not mentally stable, and he will say many things to your face that he doesn’t mean fully or exactly

To the right is a picture of Mayling Soong at the White house with FDR and Eleanor Roosevelt. While she was a regular guest at the White House it was also clear to the China Lobby that FDR had no intention of providing increased support to Chiang or cutting off oil to Japan.

To the left is a color image of Eleanor Roosevelt with Madame Chiang Kai-shek on the lawn at the White House. Mayling Soong's access to the White House came to an abrupt end when Truman became president.

Mao emerges victorious in Chinese Civil War

At the urging of Hurley and Stalin, Mao sent Zhou Enlai to Chunking in late January of 1945 to discuss terms with Chiang and Hurley but Chiang refused to share any power with Mao. He further appointed several hard-line opponents of Mao to official posts. As opposed to telling his boss the truth, Hurley reported that negotiations were “right on track” (1 p. 321) Service continued to be very outspoken regarding Hurley’s incompetency and dishonesty writing amongst other things, “It is essential that we get PH [Pat Hurley] out of the chair he now holds.” Hurley was a “bull in a China shop… the antithesis in this delicate situation of what a good servant of the American government should be.… He is an idiot playing with fire. I may sound strong. But I’m not alone in thinking these things.” (18)

In February of 1945 with ambassador Hurley and General Wedemeyer on board a plane to Washington to address what they feared FDR might have promised Stalin at Yalta, charge d’affaires George Atkinson was left in charge and did something truly unprecedented. Atkinson devised a manifesto to be signed by the embassy’s political officers that was a protest against the policies of the Ambassador and the President. It was drafted by John Service at Atkinson’s direction on February 28 and started out, “This telegram has been drafted with the assistance and agreement of all the political officers of the staff of this embassy and has been shown to General Wedemeyer’s Chief of Staff, General Gross.” The key points it made were; (1) The goals against Japan were not being achieved, (2) The administrations absolute commitment to Chiang gave him effective control over the situation regardless of what he did or didn’t do, (3) Mao could help the US defeat Japan, and (4) Mao was becoming convinced that FDR was “committed to support Chiang alone”. (1 p. 322) The cable went on to say that Mao could support American forces landing on China’s Pacific Coast and concluded that Mao should be “helped by us rather than seeking Russian aid or intervention” and the FDR should inform Chiang that “military necessity requires that we supply and cooperate with the Communists and other suitable groups who can assist the war against Japan.” (16 pp. 358-63) After the cable was sent, Service wrote in a letter to his mother, “We may become heroes—or we may be hung.” (19 p. 121) In one of Service’s last conversations with Mao, Mao restated that “Chiang was incapable of improving the condition of China’s masses” and that the United States was his choice to help rebuild China. (1 p. 323)

At this point Roosevelt was in declining health and Hurley did all he could to reinforce the China illusion to his boss. Roosevelt remained an astute politician and knew that the China Lobby’s visions of a China united under Chiang and the Soong’s resonated with a large segment of the population and that “communist” was becoming an increasingly toxic label. As one of FDR’s last acts, he ignored the plea of the China Hands and continued to stand behind Chiang as the sole leader of China (1 pp. 326-7). This ensured a civil war that would cost millions of lives but couldn’t change the course of history. When Ambassador Hurley briefed Churchill of this decision he referred to FDR’s thinking as the “Great American Illusion”. (20 p. 304)

FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was a friend of Hurley along with being a supporter of Chiang and the China Lobby. He suspected magazine editor Phillip Jaffe of being a communist sympathizer and illegally bugged his hotel room in Washington DC. Service was in DC and giving background briefings to journalists at the direction of Lauchlin Currie. Service went to Jaffe’s hotel room the evening of April 19th, 1945 and offered to provide him a couple of unclassified documents on Chiang and Mao. Service was arrested in June and subject to seven State Department investigations all of which cleared him. (1 pp. 328-9)

At 7:00 p.m. on August 14, 1945, President Truman announced the surrender of Japan. Mayling Song followed that announcement broadcasting from her sister’s (Ailing) Mansion in New York saying, “Now that complete victory has come to us, our thoughts should turn first to the rendering of thanks to our creator and the sobering task of formulating a truly Christian peace.” (21) When Hurley returned to Washington in September he came under some criticism from a few congressmen saying that he committed the US to armed intervention in China. Hurley then turned in his resignation into Truman. (1 p. 334)

The US media and military (and electorate) remained ignorant of Mao or his strategies. Chiang’s capture of Yan’an in 1947 was reported as a strategically significant victory when, in fact, it was a trap. In June of 1948, Mao and Chiang had about the same number of men and armaments but in October 300,000 of Chiang’s troops defected to Mao. Mao eventually turned to the Soviets for support which was seen as confirming the belief that he was a pawn of the Soviet Union and that his success was part of a global communist plot. In November of 1948 Chiang sent an urgent plea for more support warning that Mao’s forces were close to taking Shanghai and Nanking. (1 pp. 334-5) Even the Joint Chiefs recommended against further aid observing that it was unlikely this would even buy more time. Mayling arrived in Washington at the end of 1948 demanding three billion more dollars in US aid and Truman would not see her for nine days and would not let her stay at the White House as Roosevelt had done. He had come to refer to Chiang as “Generalissimo Cash My Check” (22 p. 564) After failing to get further US support, the Soong’s didn’t give up but sought ways to leverage the evolving US political climate to their advantage. The isolationist “Old Right” was still alive trying to gain control of the Republican Party but the anti-communist crusade was gaining strength amongst other Republican factions as Senator McCarthy was coming to prominence. Hannah Pakula summarized this in her book “The Last Empress” saying, “The Republicans took on the fight against the Communists as a moral cause; the military men were concerned about a future conflict with the USSR; and the churchmen embraced it as a struggle against the Antichrist in Asia.” (22 p. 577)

After Japan’s surrender it was forced to return Taiwan (or Formosa) to China and Chiang, with US support, went about taking it over. Chiang’s people took over the economy and displaced the islanders with mainlanders. Before long the Taiwanese economy was in as bad a shape as mainland China’s. By January of 1949 it was clear that the end had come and Chiang prepared to flee to the island after transferring what remained of the government’s gold reserves to Taiwan. The US then declared Taiwan to be the real China. (1 pp. 337-9) On October 1st of 1949 Mao Zedong overlooked Tiananmen Square with Sun Yat-sen’s widow Chingling Soong standing near him announced his rule from the traditional home of the “Son of Heaven”. Mao proclaimed that China would “never again be an insulted nation.” (1 p. 338)

The Time Magazine cover to the left was from 1937 and is significant in the media presence it represented. Time and Life were published by Henry Luce who was a missionary child and helped maintain a constant media image to the American public even after any reasonable person who have recognized Chiang was not going to be able to control China.

To the right is an image of Patrick Hurley, US Ambassador to China in 1944 and 45. He played a key role in recalling General Stilwell and was an ardent supporter of Chiang and the China Lobby. He did all he could to insulate FDR from any inputs that may have caused him to question his "only Chiang" strategy.

The picture above is of John Service, one of the embassy officers referred to as "China Hands". He lived most of his life in China and was a fierce opponent of his boss, Ambassador Hurley. He drafted a telegram signed by all embassy political officers protesting the policies of Hurley and the administration, It was a longshot that had no impact on the course of US policy. This ensured a civil war would follow.

The image to the right is of Mao Zedong on October 1, 1949 reading the proclamation of the founding of the People's Republic of China. He was overlooking Tiananmen Square with Sun Yat-sen’s widow Chingling Soong standing near him. He announced his rule from the traditional home of the “Son of Heaven”. Mao proclaimed that China would “never again be an insulted nation.”

Background of the Korean Conflict

During this time period Korea cannot be addressed apart from China as Korea, Japan, and China became highly intertwined starting at the beginning of the 20th century. In the 1890’s a major prize in the region was the railroad concession that was pursued by the American China development corporation. The company was founded in 1895 and represented a consortium of American financial interests including, the Morgan’s, the Rockefeller’s and Kuhn, Loeb, and Co (23). The prize was a Peking-Hankow rail route across Manchuria. This was ultimately unsuccessful, however, as a Russian and Belgian syndicate backed by France and Russia won the concession for the project. This then led to a more aggressive U.S Asian policy where the US hoped to push the Russians out of Manchuria. Theodore Roosevelt saw the Japanese as being culturally and ethnically superior to both the Chinese and the Slavs (Russia) along with the rest of Asia (24 p. 63) and used them as a US surrogate to accomplish this objective. He encouraged and assisted the Japanese to attack Russia in the Russo - Japanese War which was decisively won by Japan preventing Russia from extending their naval presence to the Pacific. Roosevelt was ecstatic at this outcome and then working with the Japanese leaders encouraged them to sue for peace before the full size and force of Russia could be brought against them as Japan lacked the resources and economic strength to sustain such a fight (24 pp. 67-71). For this, Roosevelt earned a Nobel Prize. With American support Korea was effectively turned over to the Japanese as a colony and Japanese economic interests in Manchuria were widely acknowledged and not discouraged.

Following Versailles the victorious powers of Japan, England, and the United states became less coupled and became competitors in Asia and China along with Russia which had always been an Anglo-American adversary in this region. This, along with changes in military technology and mission, created a naval arms race[1]. Anglo-American Rapprochement ebbed with subsequent administrations following Theodore Roosevelt and prior to Franklin Roosevelt being less inclined to act as an instrument of British elite foreign policy and the American public broadly rejecting this sort of deep association. The Wilson administration was resentful of France and England for the outcome of Versailles and the rejection of his 14 point plan and was the first to start expanding their fleet. Both English bases off the coast of Central America along with the American policy of absolute freedom of navigation were points of contention between America and England (25 pp. 287-90). The first conflict between the US and Japan arose when the US disputed Japan’s control of former Germany colonies that England had promised it as a reward for their entry into the war against Germany (25 p. 287)

Korea was an unusual colony in that it became a colony after there was a move for imperial powers to decolonize their foreign possessions and it had the all the characteristics of a natural civilization state including common ethnicity, common culture, common language, and recognized national boundaries since the tenth century (26 p. 13). When the Japanese took over Korea in 1910 they went about substitution of all these things. A Japanese ruling elite was substituted for Korean scholar-officials, a central state was put in place of the old government administration, a Japanese education system replaced the Confucian classical education, and eventually even the Korean language was replaced by Japanese. Some Korean leadership did remain in place but only by conforming to the colonizers. (27 p. 13)

Fighting on the Korean peninsula started in 1931 when Japanese forces invaded the northeast provinces of China and established a state in Manchuria, native home for the rulers of the Qing dynasty, known as Manchukuo. They quickly faced a loosely organized resistance in which recent scholarship has determined were principally made up of Koreans. (26 p. 72) The Japanese developed a minority of Koreans who would collaborate with them in identifying members of the resistance. By the md-1930's Kim il Sung became the leader of the resistance forces and he was known as being a capable and effective leader and his heirs trace their legacy back to this point. (26 p. 65) This area produced the two most significant leaders of post WWII Korea, Kim iI Sung and Park Chung Hee, and several leaders of post war Japan like Kishi Nobosuke who was responsible for munitions in Manchukuo and later worked with Shiina Etsusaburo and several others in the mid-1950s to form the mainstay of the Liberal Democratic Party that was the leading element of Japan’s unusual one-party democracy. (26 p. 66) Like other peasant uprisings in Asia it could be characterized in a variety of ways; communist, nationalist, rogue state but above all else it was anti-Japanese.

To the North Koreans it was less the Japanese than their Korean collaborators that mattered – they were blood enemies. The war in the 1950’s was a way to settle with the South Korean Army, many of whom had served the Japanese. The Americans had little knowledge of this initially and, when they did, it was no longer something that could be addressed (26 pp. 66-7). Two separate Korea’s were forming in the early 1930’s and in this conflict, neither side gave quarter. Under Japanese rule there was a beginning of an urban middle class with department stores (Hwashi) movie theatres, bars and restaurants. 75% of the population was still peasants and as the groups mixed, the contrast was stark. This was captured in a 1934 novel by Kang Kyong-ae titled Wonso Pond. (26 p. 68)

The political landscape in the 1930’s both in Europe and in Asia left few good choices with the extremes on both the left and right dominating the political landscape which is the environment that the North Korean leadership developed in as they established a beginning of a guerilla state. Both sides were willing to do “whatever it took”. Japan’s counter insurgency was just as ruthless. Their principal strategy was to separate the resistance from their supporters. Winter worked in favor of the Japanese as it made the insurgents stationary while the counter-insurgency was still able to move (26 pp. 70-1).

[1] The Panama Canal in particular posed a problem to the US in light of the ever larger naval vessels that were being produced.

This is a map from the time period that shows the advance of Japan across Asia. Korea became effectively a Japanese colony after the Russo-Japanese war in 1904-5. The Japanese were by far the most westernized of the Asian societies and were frequently referred to in America as "Yankees of the Far East". Japanese leadership was generally Ivy League educated. The Japanese were in Korea long enough that they gradually replaced Korean culture and created a modern Korean middle class society for Koreans that adapted to Japanese rule. This society existed side by side with agricultural peasants.

Korea under Military Occupation

FDR’s plan for dealing with Korea after the war was a four-power “trusteeship” (the United States, the USSR, Britain, and Nationalist China) to replace Japanese interests with American interests, while recognizing the Soviet Union’s legitimate concerns in a country that touched its border. By 1942, however, State Department Planners, afraid of losing Korea, began making plans for a full or partial military occupation. Roosevelt’s view was for a long trusteeship and he presented this several times in discussions with Churchill and Stalin. After the war came to an abrupt end and Roosevelt was gone, the State Department pushed through the occupation policy. (26 p. 127) Comparing this to the Russians in Poland the principal difference was Poland was governed by Poles aligned with Russia while Korea was governed by the US with a hand selected ruler.

The initial challenge for the Americans was to come up with enough non-communists who would align with the Americans to go about forming some sort of interim government. Within a week after arriving in Seoul, the head of XXIV Corps military intelligence, Col. Cecil Nist, identified “several hundred conservatives” who might make good leaders of postwar Korea. The challenge was that most of them had collaborated with the Japanese and it was unclear how quickly that would be forgotten. The history of the local candidates led Hodge to seek a patriotic figurehead that the OSS found in Syngman Rhee who was an exile living in the US. Rhee was flown to Tokyo where he met with MacArthur and was then transferred to Seoul in October of 1945. Rhee had been gone from Korea so long he had few close relatives there but he understood American politics and convinced his American handlers that he was their only viable option. (26 pp. 128-9)

Two years into the occupation the OSS had been morphed into the CIA which issued a report saying that South Korean political life was “dominated by a rivalry between Rightists and the remnants of the Left Wing People’s Committees,” described as a “grass-roots independence movement which found expression in the establishment of the People’s Committees throughout Korea in August 1945.” (27 p. 129) It went on to observe that the ranks of the “rightists” are provided by “that numerically small class which virtually monopolizes the native wealth and education of the country”. The report concluded “Extreme Rightists control the overt political structure in the US Zone” principally through the agency of the Japanese-built National Police, which had been “ruthlessly brutal in suppressing disorder.” The structure of the southern governmental bureaucracy was “substantially the old Japanese machinery,” with the Home Affairs Ministry exercising “a high degree of control over virtually all phases of the life of the people.” (27 pp. 129-31) (28) (29)

While both the US in the South and the Soviets in the North supported domestic forces that were sympathetic to their world views, the American occupation leaders went beyond that by establishing a colonial national police force, an Army, and installing a Korean exile living in the US as the political leader, and was establishing a separate government while the Soviets were slow to take these measures in the North. The “Korean People’s Republic” independent from the North was proclaimed on September 6, 1945. This, in turn, led to the establishment of hundreds of “People’s committees” in the countryside. (27 p. 131) The occupation commander, General Hodge who had a solid history and reputation, but was worried about the political, social, and economic disorder he perceived around him, took action to control it. He collectively saw leftists, anti-colonialists, populists, and land reform advocates in the South as “communists”. Against direct instructions he began to form a South Korean Army in November 1945 and In Spring of 1946 he issued his first warning of an impending invasion from the North. (27 p. 132) Forced re-education was also implemented in some areas.

Resistance to the measures taken during the occupation period in southern Korea was much greater in the South than in the North and should be considered indigenous to the South. A major rebellion took place in October and November 1946 which was the culmination of months of conflicts with locally powerful people’s committees. In October 1948 a large rebellion occurred in and around the southwestern port of Yosu with the guerrilla resistance having developed quickly and was predominantly indigenous to the south (26 p. 134). The rebellion was centered in southwestern Korea and on Cheju Island and kept the Korean Army and Korean National Police occupied throughout 1948 and 1949. US estimates of Korean deaths in Cheju Island from the period range from 30,000 to 60,000 but more recent estimates are as high as 80,000. By early 1947 Kim Il Sung was providing troops to fight on the Communist side in the Chinese civil war, and in the next two years tens of thousands gained important battle experience. These became the main shock forces in the Korean People’s Army, forming several divisions that fought in the Korean War (26 p. 134).

The tendency for the occupation government to support the Korean right was largely driven by fear of and opposition to the Korean left and wasn’t supported by the State Department. By 1947 with containment becoming the policy in Washington, this had the effect of supporting the occupation policies. Quoting from author Bruce Cummings, “Internal documents show that South Korea was very nearly included along with Greece and Turkey as a key containment country; although never admitted publicly, in effect it became a classic case of containment in 1948–50, with a military advisory group, a Marshall Plan economic aid contingent, support from the United Nations, and one of the largest embassy operations in the world.” (26 pp. 134-5) A related factor in the handling of Korea was that Japan was being reconstructed to return to being an industrial power which brought about the same raw material supply issues that had constrained Japan before the war. This, in turn, would require access to its old colonies for materials and markets. (26 p. 134)

Through the time leading up to the war there were concerns about the Rhee government’s human rights abuses but by 1950 he was seen as having defeated the communist rebellion and in this case the end was more important than the means. Quoting from author Justin Raimondo who was a regular contributor to the American Conservative and wrote several book on the period:

We were fighting on behalf of Sungman Rhee, the US-educated-and-sponsored dictator of South Korea, whose vibrancy was demonstrated by the large-scale slaughter of his leftist political opponents. For 22 years, Rhee’s word was law, and many thousands of his political opponents were murdered, tens of thousands were jailed or driven into exile. Whatever measure of liberality has reigned on the Korean peninsula was in spite of Washington’s efforts and ongoing military presence. When the country finally rebelled against Rhee, and threw him out in the so-called April Revolution of 1960, he was ferried to safety in a CIA helicopter as crowds converged on the presidential palace.

Syngman Rhee (left) was a Korean expatriate who had lived in America for over twenty years before being returned to Korea and installed as a native leader of the US occupation government. Rhee did understand US politics and the role of the press.

(Getty Images)

General Douglas MacArthur (right) was in charge of the Asian theatre and approved the selection of Rhee. The difficulty the US faced if forming a government that appeared to be Korean was that the majority of people seen as being "conservatives" had collaborated or worked with the Japanese.

(Getty Images)

The Time Magazine cover of Rhee shows how he was presented to the American audience in Time and Life which were key publications associated with the "China Lobby". While the outcome in China as Rhee came to power was increasingly certain many had not yet given up on the vision.

June 1950 – The War Begins

The official start of the war was on the inaccessible Ongjim Peninsula, northwest of Seoul, the night of June 24 and 25, 1950. There had been border fighting in this area since May and, lacking observers, both sides claimed they were attacked first (26 p. 24). The initial US news reports were that North Koreans initiated a surprise attack but there were intelligence reports of troop buildups well prior to that that were apparently dismissed. In a Biography of MacArthur written by John Gunther, the general is quoted as saying, “On the morning of June 25, the North Koreans launched an attack by no fewer than four divisions, assisted by three constabulary brigades; 70,000 men were committed, and about 70 tanks went into action simultaneously” (30 p. 40). While it is unclear who attacked who and in what order, it is now known from Soviet documents that Pyongyang had determined to escalate from a border war to a full scale conventional warfare many months before June 1950. The guerilla struggle in the South was inconclusive, and any event along the border could be portrayed to justify and invasion. (26 p. 26)

Looking at South Korea we find a similar situation in terms of intent. Just a week before the invasion John Foster Dulles visited Seoul and the 38th parallel where there are pictures of him peering of across the no man’s land that were widely published at the time. He was a roving ambassador at the time and was the favorite for becoming Secretary of State under Truman although being a Republican. His selection would have been an attempt at bipartisanship to counter the interventionalist Republicans who were using “Who Lost China?” as a rallying cry. Dulles met with Syngman Rhee during this visit and Rhee not only advocated for full US involvement but wanted to overrun the North and unify Korea but there is no indication that Dulles gave any commitment to that. (27 pp. 23-25) Dean Acheson who was Truman’s Secretary of State was asked the question at a seminar several years after the war, “Are you sure his presence didn’t provoke the attack, Dean? …. There has been comments about that—I don’t think it did. You have no views on the subject?” His response was simply “no”. (26 p. 26) So although provocative, the significance of this spectacle remains inconclusive.

As cited in an article by Justin Raimondo, professor Mark E. Caprio speaking at the University of Tokyo reported Rhee also made his case to launch an invasion clear back on February 8th, 1949 when he met with US Ambassador John Muccio and Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall in Seoul. Caprio states, “Here the Korean president listed the following as justifications for initiating a war with the North: the South Korean military could easily be increased by 100,000 if it drew from the 150,000 to 200,000 Koreans who had recently fought with the Japanese or the Nationalist Chinese. Moreover, the morale of the South Korean military was greater than that of the North Koreans. If war broke out he expected mass defections from the enemy. Finally, the United Nations’ recognition of South Korea legitimized its rule over the entire peninsula (as stipulated in its constitution). Thus, he concluded, there was "nothing [to be] gained by waiting “ (31)

What had stopped Rhee from launching an attack was American reluctance to supply him with the arms and financing he would need and the terms or constraints that were to go along with it. The general US policy had been to provide Rhee with enough to control the South but no more than that. On the Communist side of the conflict there was also uncertainty on the Korea problem. Stalin was skeptical of Kim il Sung’s claim that he could achieve victory in three days and the Russians position was that they would provide aid but no direct intervention (31). China’s Mao offered support but it wasn’t provided until the US had directly entered the war and advanced well into North Korea. Mao felt there was a debt owed to the Korean role fighting the Japanese and supporting Mao in the Chinese civil war. Neither Stalin nor Truman were anxious for the conflict but probably saw it as inevitable and tried to manage the media presentation to their respective benefit. (31)

At this same time, the Truman administration was still trying to deal with the Chinese Nationalist problem which was a political disaster that was characterized by far more constraints than opportunities. Chiang and his remaining followers had fled to Taiwan in January of 1949 and there was a real possibility that Mao’s forces would pursue them and take the island. Chiang, the Soong’s and the China Lobby, instead of giving up and accepting defeat, were still active politically and economically and they had influential supporters in the interventionalist side of the Republican Party. The China Lobby had developed strong support in the Roosevelt administration including Stimson, Acheson, and even FDR and this held up into the last phases of WWII but it had been clear to any reasonable observer from mid 1945 that Chiang could never defeat Mao and was never capable of forming a state in the first place. For the American public however, the “China Mirage” created by the Soong’s and the China Lobby was deeply ingrained and wouldn’t die easily. Further, the faith was closely associated with all types of Protestant denominations giving the belief in a westernized and Christianized China a strong religious component that made it difficult to even question in the minds of many. Joe McCarthy saw Acheson and Truman as the major impediment to ongoing financial and possibly direct military support and he was trying to use the hearings to get at Acheson. Against this backdrop and with the crisis in Korea, there was a developing plan to launch a coup against Chiang Kai-shek. Dean Rusk met with several Chinese officials in New York the evening of June 23, 1950 at the Plaza Hotel in an attempt to form a government to replace the Chiang regime. Rusk and Acheson wanted to have a reliable leader in Taipei that would help justify keeping the island separate from the mainland. (26 pp. 27-28)

When the fighting started it went badly for the South and it appeared as if Kim il Sung’s claim that he could achieve victory in three days might have some merit. The ROK 7th division was headquartered at the critical invasion route town of Uijongbu but hadn’t committed its forces by the morning of June 26. It was probably waiting to be reinforced by the 2nd Division coming from the north. When the 2nd Division did arrive, it collapsed creating a gaping hole in the Uijongbu Corridor that the KPA units continued to pour through during the afternoon and evening of the 26th immediately jeopardizing the capital of Seoul. An American official describing the events wrote, “The failure of the 2nd Division to fight” was the main reason for what would be the quick loss of Seoul (26 p. 30). President Rhee attempted to flee the city with his top officials as early as Sunday night and the entire ROK headquarters relocated south of Seoul by June 27th without the Americans being notified. As military morale collapsed and civilians panicked, a KPA invasion force of only 37,000 took the city. By July 1, at least half of the ROK soldiers were either killed, captured, or missing. (26 pp. 30-31)

The image to the right is of a New York Times headline regarding the beginning of the Korean War "To Save Humanity from the Deep Abyss"

The image to the right is of John Foster Dulles looking across at North Korean troops. It is unclear what if any significance this had but his visit was widely covered in the press. (wikipedia)

The image to the left is a map of troop movements in the Korean War in August of 1950. The swings were rapid and dramatic (britanica)

The Americans Step into the Fight

Because of the rapid and near complete collapse of Rhee’s military, the Americans were then left with a decision to step in or walk away. As important as the decision itself however, was the process by which it was made and the precedent it would establish for the future as the US would become less of a constitutional republic. Dean Acheson, who dominated the decision making, soon committed American forces to fight (26 p. 31). Of note here is that Acheson was also one of the key players in violating the policy of FDR and Secretary Hull to provide the Japanese with oil prior to Pearl Harbor to keep them from expanding to Southeast Asia. Acheson determined to take the matter to the UN the night of June 24th before he had even notified President Truman of the fighting and then told Truman there was no need to have him back in Washington until the next day. During an emergency meeting at the White House on the evening of the 25th, Acheson argued for increased military aid to the ROK along with USAF cover for the evacuation of Americans and placing the 7th Fleet between mainland China and Taiwan. The last item intertwined a matter not directly related to the fighting in Korea. This would in effect permanently divide China and would also defuse a building domestic political problem with the more radical Republican interventionalists. On June 26th, Acheson, working alone, came up with the plan to implement all of this which was approved by the White House that evening. (26 p. 31)

Acheson’s reasons for stepping in to stop the KPA advance in the South wasn’t based so much on the inherent strategic value of Korea but was seen as an indication of American economic and military prestige saying “prestige is the shadow cast by power” and that the North Koreans had challenged American credibility. Acheson did see Korea as essential to Japan’s reindustrialization and as part of a larger “great crescent” strategy linking northeast Asia to the Middle East (27 p. 31). When Acheson’s plan went before the UN, the Soviet Ambassador to the UN, Yakov Malik, wasn’t present to use their Security Council veto to block the plan. This was seen at the time as being a boycott because the UN had failed to admit Mao’s China but there may have been more strategy at play here than that. Soviet foreign minister Andrei Gromyko, later told Dean Rusk that on the Saturday night Malik had wired Moscow for instructions and got a message directly back from Stalin (for the first time). Stalin simply said, “Nyet, do not attend” (32 p. 211). There was no further explanation but it was likely that Stalin saw this as an opportunity for the Americans to be drawn into a long term conflict that couldn’t win or escape from (26 p. 32).

The Joint Chief of Staff remained “extremely reluctant” to commit ground forces to the fighting right up to June 30th and weren’t consulted by either Acheson or Truman. There was a strategic aspect of this where they saw themselves in a potential trap in a global struggle with the Soviets but it was also based simply on troop strength. The US Army had a total of only 593,167 troops plus 75,370 Marines. North Korea would readily mobilize 200,000 combat soldiers in the summer of 1950 apart from the vast resources of Mao’s Armies just a short distance away (26 p. 33). The factor that drove the deployment was MacArthur’s conclusion after visiting the frontlines that the ROK forces had stopped fighting and that the South Koreans “did no fighting worthy of the name” but rather broke and ran. Still the Americans had no idea of the effectiveness of the forces they were up against. MacArthur is quoted as saying, “I can handle it with one arm tied behind my back,” which he followed up with, speaking to John Foster Dulles, that if he could only put the 1st Cavalry Division into Korea, “why, heavens, you’d see these fellows scuttle up to the Manchurian border so quick, you would see no more of them.” (26 pp. 33-34)

These sorts of statements can be attributed to male bravado or hubris but there is also a reflection of racial attitudes as well. Author Bruce Cummings projects this onto “White America” in a general sense and spends several pages building this logic which was fairly ordinary for any history book published in the early part of the 21st century in the west, but the attitudes of America’s “Power Elites” represented a specific class of American society generally with fairly precise cultural, ethnic, and even religious characteristics. This subject was examined by C. Wright Mills in the “Power Elite” in 1956 (no postmodern influences) and specifically with regard to Acheson, Kennan, and the “Wise Men” in “The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World they Made” by Walter Isaacson and Evan Thomas. The elite American decision makers of the era bore no empathy towards an Asian peasant but neither did they to a Scot-Irish subsistence farmer in Arkansas or a German or Irish factory worker in the upper Midwest. They did see themselves as destined to rule and were in most respects more like their English counterparts than to “ordinary Americans” in what would come to be known as the “flyover states” across America.

Throughout the summer of 1950 the Americans suffered one defeat after another and were pushed across all fronts. By the end of July, American and ROK forces outnumbered the KPA forces at the line of contact, 92,000 to 70,000 (47,000 were Americans), but in spite of this, the retreat continued. (26 p. 36) In early August the 1st Marine Brigade joined the fight which halted the KPA advance and the front stabilized until the end of August. The perimeter had its northern anchor on the coast in the vicinity of Pohang and its southeastern anchor around the Chinju-Masan region. The center was at Taegu which was seen as the main point for stopping the advance but the Northeast was probably the key point for stopping the KPA from occupying Pusan and unifying the peninsula. Not pressing the advantage to the north may have been a key tactical mistake for the North (26 pp. 36-7). The pause could also have been to isolate Seoul and watch the Rhee regime simply collapse but, regardless of the reason, it gave McArthur time to organize a defensive line in the southeast that held. By this time there were 83,000 Americans, 57,000 Koreans and British along the front. MacArthur had committed most of the battle ready divisions in the entire American armed forces to Korea. The Americans now had vastly superior artillery and complete control of the air. (26 p. 38) The Americans were facing a new kind of guerilla warfare that they hadn’t encountered in Europe where they could be attacked from any direction at any time. Villages that were suspected of harboring or supporting guerrillas were burned to the ground, usually from the air. Cities and towns thought to be leftist were simply emptied of their population through forced evacuations. All but 10 percent of civilians were moved out of Sunchon. (26 p. 37)

To the right is Soviet UN Representative Yakov Malik in an image from 1952. Malik wasn't present at the UN vote on Acheson's plan to step into Korea a few days after the war broke where he could have used their Security Council veto to block the plan. When Malik asked for direction on whether or not to attend Stalin personally answered “Nyet, do not attend” .

To the left is Secretary of State Dean Acheson who was one of the "Wise Men" under Roosevelt. He was principally responsible for US policy during the first year of the war and made the minute by minute decisions at the outset. Acheson’s reasons for stepping in to stop the KPA advance in the South wasn’t based so much on the inherent strategic value of Korea but because it was seen as an indication of American economic and military prestige saying “prestige is the shadow cast by power”

Resistance to Truman’s and Acheson’s Korea Policy

While these events were going on in Korea the political fight in the US regarding the undeclared war was far from over although most of the drama wouldn’t happen until the new session in 1951. The isolationist wing of the Republican Party, referred to as the “Old Right”, led by Senator Taft was not accepting the usurpation of Congressional authority and they were a bare majority at the time. Senator Taft opposed the cold war and the creation of NATO reasoning that a massive standing army surrounding Russia from Norway to the Middle East would lead Russia to conclude that a buffer of satellite countries was necessary for their own defense. The interventionist side was led by Senator John Dulles, closely connected to Wall Street and the Rockefeller family, and brother of Allen Dulles. Taft, along with many interventionist Republicans, opposed mounting US involvement in Asia defeating Truman’s $60 million aid bill for South Korea by one vote (33 p. 92) In January of 1950. This decision however was reversed by the efforts of Representative Walter Judd (R, Minn), who was a former missionary and leader of the China lobby in Congress. For the Old Right the Korean War was to be the final fight, the “hill to die on”. The entire liberal and progressive left, except for the communists, had bought into the concept of UN authority and “collective security against aggression” (33 p. 92). Representative Howard Buffet and others of the Old Right were convinced that the US was largely responsible for initiating the conflict in Korea based on secret testimony by Admiral Hillenkoeter, who was head of the CIA, and that calling the escalation in June a “surprise attack” was just a ploy to influence public opinion. He tried for the rest of his life to get this testimony declassified and released but that never happened. Hillenkoeter was fired by Truman after this incident (33 p. 93).

The issue of US support for Rhee was brought to international attention in an interview in early May with Senator Connally of Texas, who was head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, with the influential Washington World and News Report which was a weekly publication. In the interview, Senator Connally was asked whether the suggestion “that we abandon South Korea is going to be seriously considered.” The Senator then said that he thought this was going to happen “whether we want it to or not.” He also thought the Communists “probably will overrun Formosa.” The Senator was then asked, “But isn’t Korea an essential part of the defense strategy?” to which he replied: “No. Of course any position like that is of some strategic importance. But I don’t think it is very greatly important. It has been testified before us that Japan, Okinawa, and the Philippines make the chain of defense which is absolutely necessary.” (30 pp. 48-49) International headlines the next day read, “REDS WILL FORCE US TO QUITE SO KOREA, CONNALLY PREDICTS”. Rhee then called in the Associated Press for an exclusive interview in which he said, “Senator Connally must have forgotten that the United States has committed herself and cannot pull out of the Korea situation with honor.” (30 pp. 487-49)

Admiral Hillenkoeter, shown to the left, was the first Director of the CIA until he was fired by Truman. Representative Howard Buffet and others were convinced that the US was largely responsible for starting the war based on secret testimony by Hillenkoeter, who added that calling the escalation in June a “surprise attack” was just a ploy to influence public opinion. Hillenkoeter tried for the rest of his life to get this testimony declassified and released but that never happened.

The US Line Holds and the Inchon Landing

The last North Korean offensive of this phase of the war came at the end of August and it made “startling gains” over a two week period and almost broke through despite what would have appeared to have been overwhelming factors favoring the Americans. On August 28, Gen. Pang Ho-san’s forces moved to take Masan and Pusan and in the next few days, three KPA battalions succeeded in crossing the Naktong River in the central section. Pohang and Chinju were lost and KPA forces were pressing Kyongju, Masan, and Taegu. The Eighth Army headquarters had to be relocated from Taegu to Pusan and prominent civilians began leaving Pusan for Tsushima. In September Kim il Sung described the war as having reached an “an extremely harsh, decisive stage”. “After two weeks of the heaviest fighting of the war” the UN forces, “had just barely turned back the great Korean Offensive”. (26 pp. 38-39)

The next few months would see the high and low points of MacArthur’s storied career. In mid-September, General MacArthur led the tactically brilliant amphibious landing at Inchon overcoming treacherous tides that could easily ground a flotilla of ships if not executed precisely around the tides. Adm. Arthur Dewey Struble, who also led the World War II landing operations at Leyte in the Philippines and who directed the naval operations off Omaha Beach during the Normandy invasion, commanded the fleet of 270 ships in the Inchon operations landing 80,000 marines mostly unopposed initially. After heavy fighting, Seoul fell to US forces by the end of September 1950. Kim il Sung had only placed about two thousand poorly trained troops to defend the harbor and had not laid any mines. They lacked the capability to resist the invasion and began a strategic retreat. (26 pp. 38-39)

A document was recovered shortly after the Inchon landing that provided a window into the KPA’s and specifically Kim il Sung’s thinking regarding the conduct of the war to that point. It said, “The original plan was to end the war in a month…. but “we could not stamp out four American divisions.” The units that captured Seoul disobeyed orders by not marching southward promptly which gave “a breathing spell” to the Americans. Kim seemed to anticipate involvement of American ground forces but not in the quantities that were directed at him saying, “our primary enemy was the American soldiers,” but he acknowledged that “we were taken by surprise when United Nations troops and the American Air Force and Navy moved in.” (26 pp. 40-41)

The picture above gives a good representation of the massive scale on of the Inchon Landing along with the low water levels (alamy.com)

The picture below of of the First Marine Division landing unopposed at Inchon well behind enemy lines (Getty Images)

China Enters the War and Routes Allied Forces